The Wheel and the Algorithm | Part 1

What a chance encounter on an Amtrak train revealed about the nature of technological revolutions

A Conversation Between Strangers

Last Thursday, returning home from Washington, D.C., on the late train to Princeton, I found my seat occupied by a gentleman in his seventies. He was traveling with his wife, surrounded by four large suitcases, the kind meant for international journeys. The bags had wheels at the bottom, and he was holding onto them with evident concern.

Anyone who has traveled on Amtrak knows the problem: the trains lack proper restraining mechanisms for large luggage. Without someone holding them, those wheeled bags would roll across the aisle with every curve in the track.

As a good Samaritan, I offered to help secure a couple of them. We struck up a conversation.

When I asked what he did for a living, he said he was retired but had worked in LPI, or Low Probability of Intercept. I had never heard the term. He explained it succinctly:

A class of radar and communication technologies designed to evade detection, used primarily in defense systems but with some commercial applications.

In under a minute, he had compressed decades of expertise into a crisp, accessible explanation. I was impressed.

Then he turned the question back to me.

So what does AI actually do? How does it change lives?

I felt the pressure immediately. Here was a man who had just distilled a complex defense technology into sixty seconds. His wife was gathering their belongings. The train was approaching their stop. As a technology executive, I needed to compress this massive, sprawling concept into something equally elegant.

My mind raced through metaphors. And then it struck me:

AI was much like the invention of the wheel.

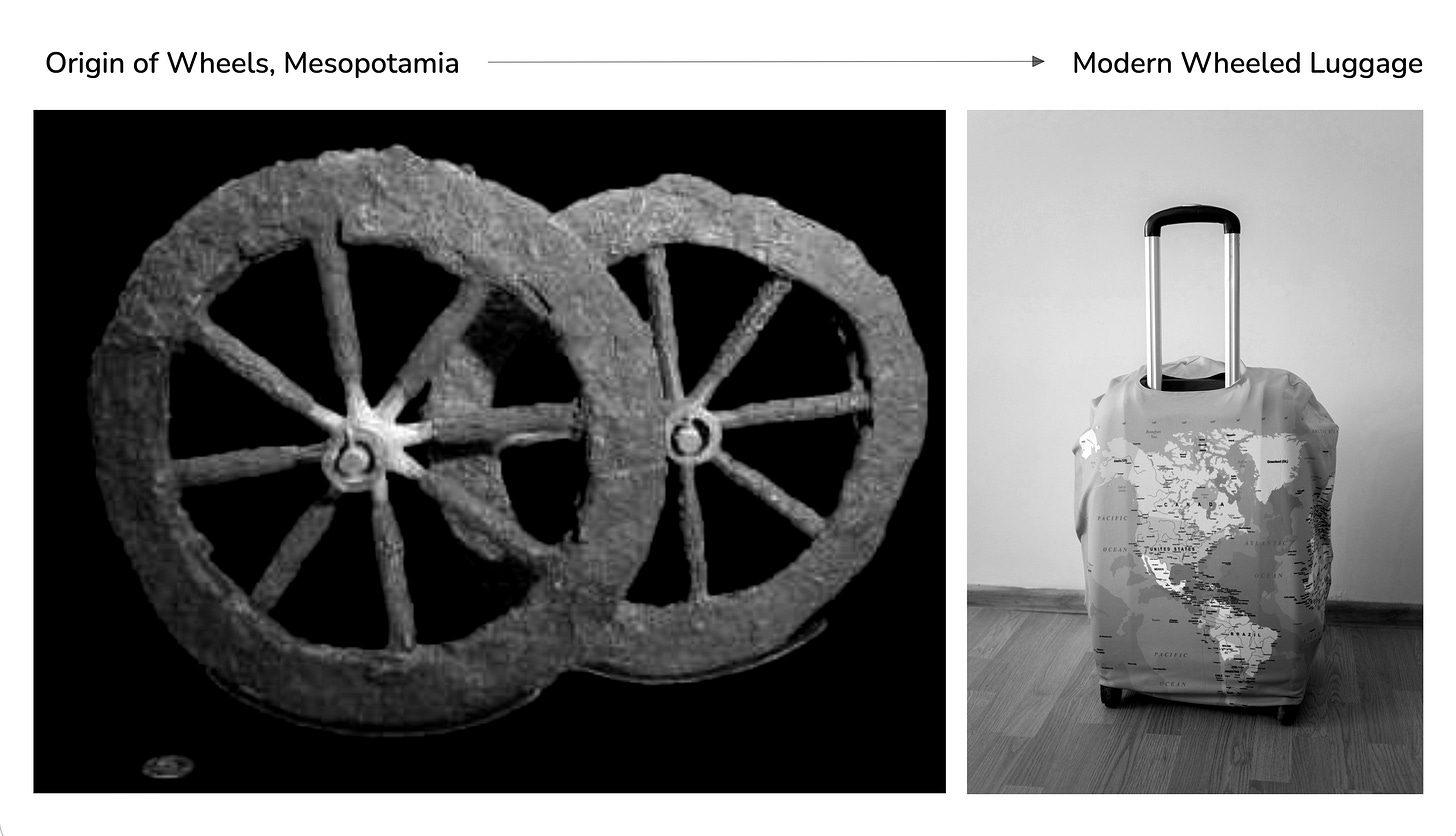

As the couple prepared to disembark, rolling their wheeled bags toward the exit, the metaphor seemed almost too perfect. He now had a fresh perspective on the casters beneath his luggage, those simple rotating mechanisms that trace their lineage back five thousand years to the plains of Mesopotamia.

I had another couple of hours in the quiet of the late-night train. I kept thinking about it. I researched the history. And the more I looked, the more I realized that the wheel’s story offers a remarkably precise lens for understanding what we are living through with artificial intelligence. Its delayed invention, its uneven adoption, and its transformative consequences all find echoes in our current moment.

The Wheel’s Mysterious Delay

The wheel appeared around 3500 BCE in Mesopotamia, modern-day Iraq. This seems early until you consider what humans had already accomplished without it. Agriculture had been practiced for millennia. Complex textiles were being woven. Boats navigated rivers and coastlines. Metallurgy had produced bronze tools and weapons. The great pyramids of Egypt were constructed by moving massive stones on wooden sledges and rollers.

The concept of something round that rolls was not a mystery. Humans had been using logs to move heavy objects since prehistory.

The breakthrough was not the wheel itself. It was the axle.

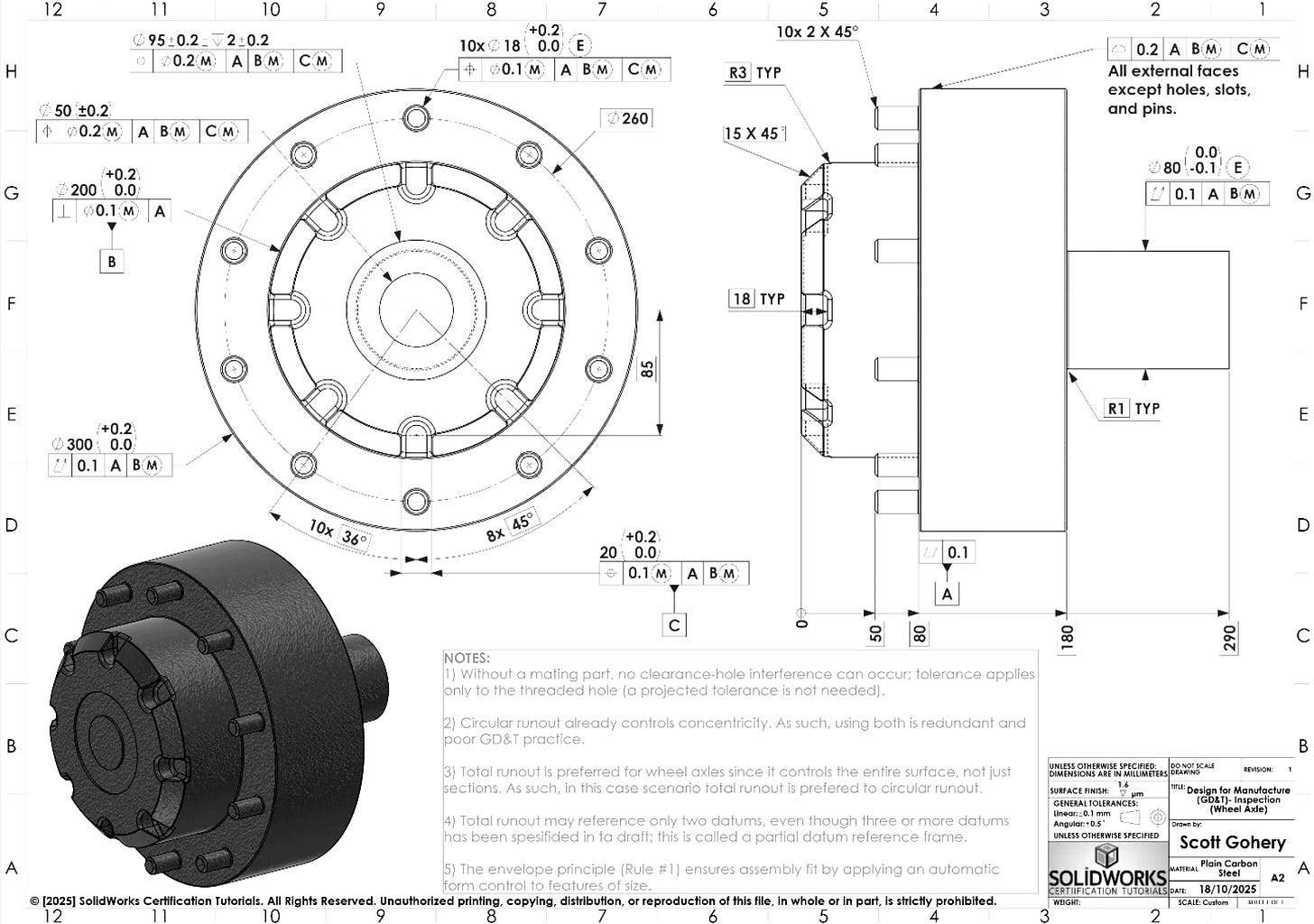

Attaching a wheel to a fixed axle, or a rotating axle to a stationary platform, required solving problems that were far from obvious. The tolerances had to be precise: too tight, and friction renders the mechanism useless. Too loose, and the wheel wobbles apart. You needed sophisticated carpentry, an understanding of lubrication, and materials strong enough to bear loads while remaining light enough to be practical.

The most likely evolutionary path ran through the potter’s wheel. Artisans spinning clay had already solved part of the rotational mechanics. Someone, we will never know who, recognized that the same principle could move objects horizontally, not just spin them in place.

But the wheel only became transformative once the surrounding infrastructure caught up. Wheels require relatively flat, cleared paths. They require draft animals capable of pulling carts. They require a density of settlement and trade that justifies the investment in building roads and vehicles. The technology preceded its widespread adoption by centuries because the ecosystem was not ready.

The Axle Problem

This is where the parallel to artificial intelligence becomes striking.

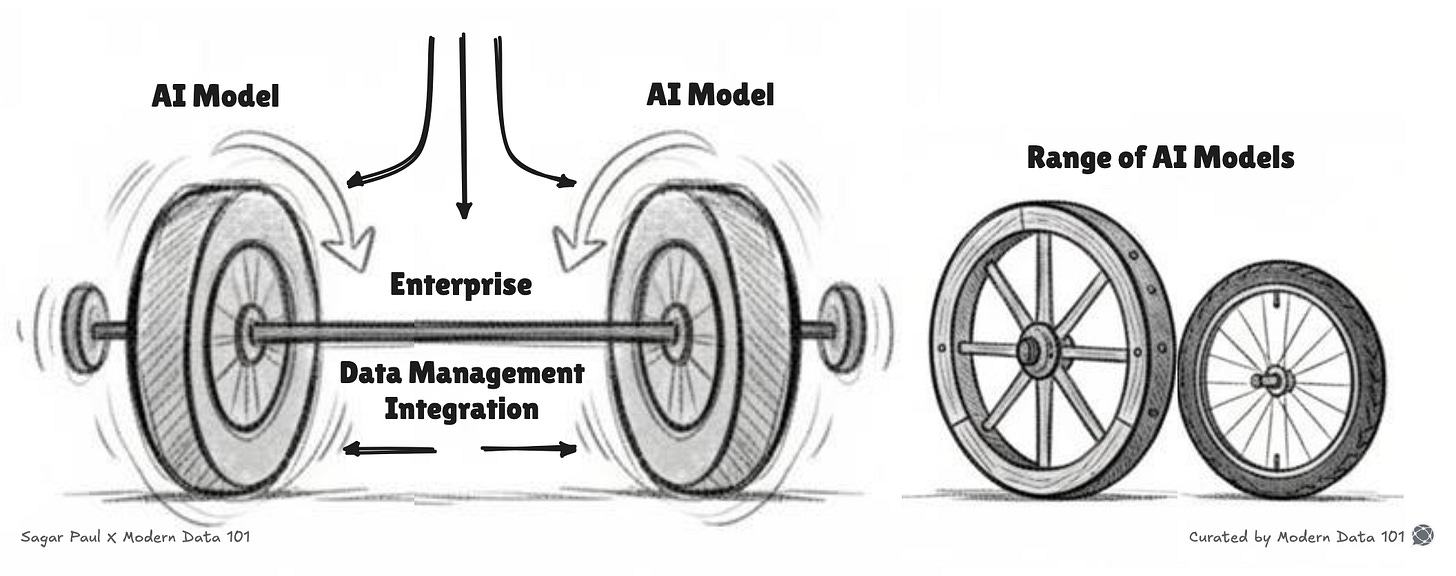

We have built the wheel. Large language models, computer vision systems, and predictive algorithms are the visible, conceptually graspable parts of the revolution. People can see a chatbot responding to questions or an image generator producing artwork and understand, at least superficially, what is happening.

But the real engineering challenge, and the reason adoption lags capability by years, is the axle.

How do you connect an AI model to existing workflows, databases, and decision-making processes?

How do you integrate it with legacy systems that were never designed to interface with probabilistic reasoning?

How do you establish the tolerances: enough autonomy for the AI to be useful, enough oversight that humans remain in control?

Just as the ancient wheel needed the right fit between hub and axle, AI needs the right fit between model and enterprise. Too tight, with too many restrictions and too much human review, and the friction eliminates any efficiency gains. Too loose, with too much autonomy and too little validation, and the system produces errors that undermine trust.

The organizations that will benefit most from AI are not necessarily those with access to the most sophisticated models. They are the ones that solve the axle problem by building the data infrastructure, the integration layers, and the governance frameworks that allow AI capabilities to actually connect to real operations.

Evidence of the Gap

If you look across industries, the pattern is consistent:

AI capabilities have outpaced adoption by years, sometimes decades.

In healthcare, AI systems have demonstrated radiologist-level accuracy in detecting certain cancers and diabetic retinopathy since 2016 and 2017. Yet most diagnostic imaging worldwide still relies primarily on human interpretation. The barriers are not technological. They are liability concerns about who bears responsibility when the AI misses something, reimbursement models that do not account for AI-assisted diagnosis, physician skepticism, regulatory approval timelines, and the difficulty of integrating new tools with hospital IT systems that were designed decades ago.

In legal services, AI-powered contract analysis and document discovery tools have been commercially available for nearly a decade, with demonstrated ability to review materials faster and often more accurately than junior associates. Adoption remains limited. The billable hour model actively discourages efficiency gains. Partners resist changing workflows that have served them well. Clients worry about confidentiality. Malpractice concerns loom.

In manufacturing, predictive maintenance systems have been available since the mid-2010s. These combine sensors and machine learning models to anticipate equipment failures before they occur. Adoption is patchy despite obvious return on investment. Factory equipment often lacks the sensor infrastructure. Operational technology teams are unfamiliar with data science. Organizations default to scheduled maintenance because that is what they know, and it is difficult to quantify the value of a failure that never happened.

In agriculture, computer vision for crop monitoring and AI-driven irrigation optimization have existed for years. Adoption among farmers remains low outside large industrial operations. Rural connectivity is unreliable. Upfront costs are prohibitive for small operations. The demographic of farmers skews older and more skeptical of black-box recommendations.

In government, AI tools for fraud detection, benefit eligibility determination, and citizen service automation exist and work. Government adoption lags the private sector by years. Procurement regulations move slowly. Political sensitivities around automated decision-making are acute. Workforces are unionized and resistant. Institutional cultures are risk-averse.

The wheel exists. The roads do not.

The Enabling Technologies

Once the basic wheel existed, rapid differentiation followed. Spoked wheels emerged for chariots, offering lighter weight and faster speeds. Solid wheels persisted for heavy carts, providing more durability under load. Potter’s wheels were optimized for rotation speed and control. Each variant was tuned for different tolerances and use cases.

We are witnessing the same pattern with AI.

General-purpose foundation models are spawning specialized variants for code generation, legal documents, medical imaging, conversational interfaces, and financial analysis. The base technology is fragmenting into purpose-built applications, each optimized for its domain.

But the differentiation that matters most is not in the models themselves.

It is in the infrastructure that enables them.

The biggest enablers in technology today are not the AI algorithms. They are the data platforms that make enterprise information accessible, governed, and ready for machine consumption. They are the integration layers that connect AI capabilities to operational systems. They are the observability tools that let organizations understand what their AI systems are actually doing. They are the security frameworks that protect sensitive data while still allowing AI to extract value from it.

A company can license the most sophisticated language model on the market, but without clean data pipelines, without APIs that expose the right information at the right time, without monitoring that catches when the model drifts off course, the technology sits idle. Like a wheel without roads.

Network Effect and Compounding Returns

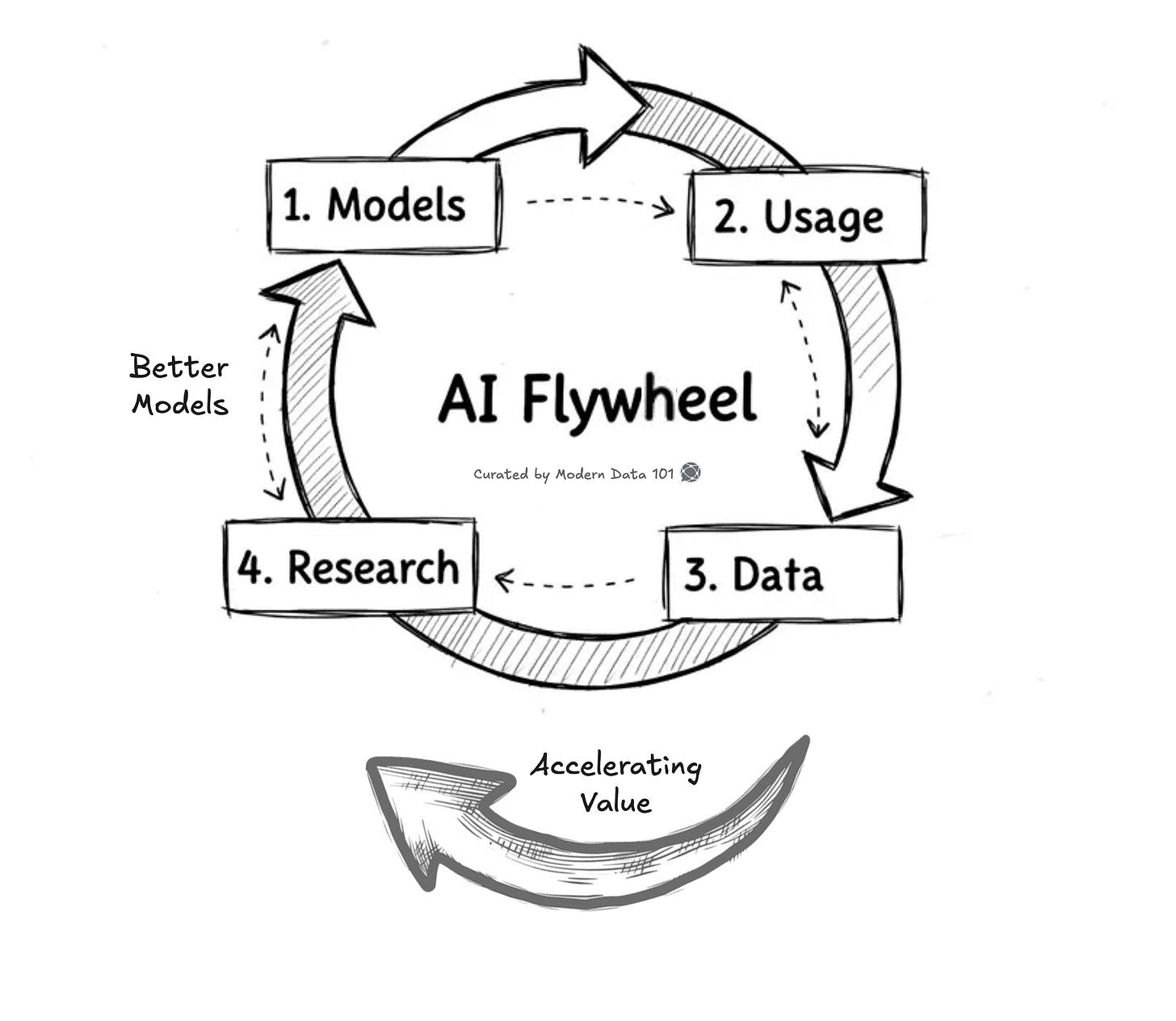

Wheels enabled carts, which justified roads, which enabled trade routes, which created demand for better wheels and more roads. Each improvement reinforced the others. The wheel did not just solve a transportation problem.

It created an infrastructure flywheel that compounded over centuries.

AI shows the same compounding dynamics, but on a compressed timeline. Better models create more usage, which generates more data, which funds more research, which produces better models.

💡 Organizations that enter this flywheel early accumulate advantages that become increasingly difficult for latecomers to replicate.

The firms that are extracting value from AI today are not necessarily the ones with the best algorithms. They are the ones who started building their data infrastructure five or ten years ago. They are the ones whose workflows were already digitized, whose data was already centralized, whose employees were already comfortable working alongside automated systems.

The AI models became powerful enough to matter only recently, but the organizations that can deploy them were preparing for decades.

This is the uncomfortable truth for enterprises that feel they are falling behind: you cannot simply purchase your way to AI maturity. The underlying infrastructure, including data governance, integration architecture, and cultural readiness, takes years to build. Starting now is essential, but expecting immediate results is unrealistic.

📝 Related Read

Resistance and Redistribution

Historical evidence suggests that some communities resisted wheeled transport because it disrupted existing porter and pack-animal economies. The transition was not purely technological but social and political. Those who made their living carrying goods on their backs or managing mule trains had every reason to oppose a technology that would render their skills obsolete.

Today’s debates about AI in creative industries, knowledge work, and professional services echo this pattern. The technology’s capability is rarely the question. The redistribution of economic value is.

Writers worry about being replaced by generators. Artists resist having their work used to train systems that compete with them. Lawyers and consultants see junior roles being automated before the senior partners have figured out how to bill for the new capabilities.

This resistance is rational. Technological transitions create winners and losers, and the losers have every incentive to slow the transition down. The political economy of adoption matters as much as the technical feasibility.

Organizations that want to accelerate their AI journey must grapple not just with technical integration but with workforce anxiety, union negotiations, retraining requirements, and the simple human reluctance to change.

Uneven Terrain

The wheel thrived in the flat, dry plains of Mesopotamia but was less useful in mountainous terrain or dense forests. The technology fit certain contexts better than others. Civilizations that lacked suitable geography or draft animals, like the pre-Columbian Americas, developed sophisticated societies without ever inventing the wheel for transport.

AI adoption will follow similar contours.

Some industries, regulatory environments, and organizational cultures will prove more hospitable than others, not because of the technology’s inherent limits but because of contextual fit.

Highly regulated industries like healthcare and financial services face compliance burdens that slow experimentation. Organizations with fragmented data landscapes cannot easily train or deploy models that require unified views of their information. Cultures that prize individual judgment and resist standardization will struggle to accept algorithmic recommendations.

This means that competitive advantage from AI will not be uniform. Some enterprises will leap ahead because their context, including their data maturity, regulatory environment, and workforce culture, is favorable to rapid adoption. Others will lag not because they lack access to technology but because their terrain is rougher.

The strategic question for executives is not whether AI is powerful (it is) but whether their organization’s terrain is suitable. If it is not, what investments are required to clear the ground?

Levers and Limits

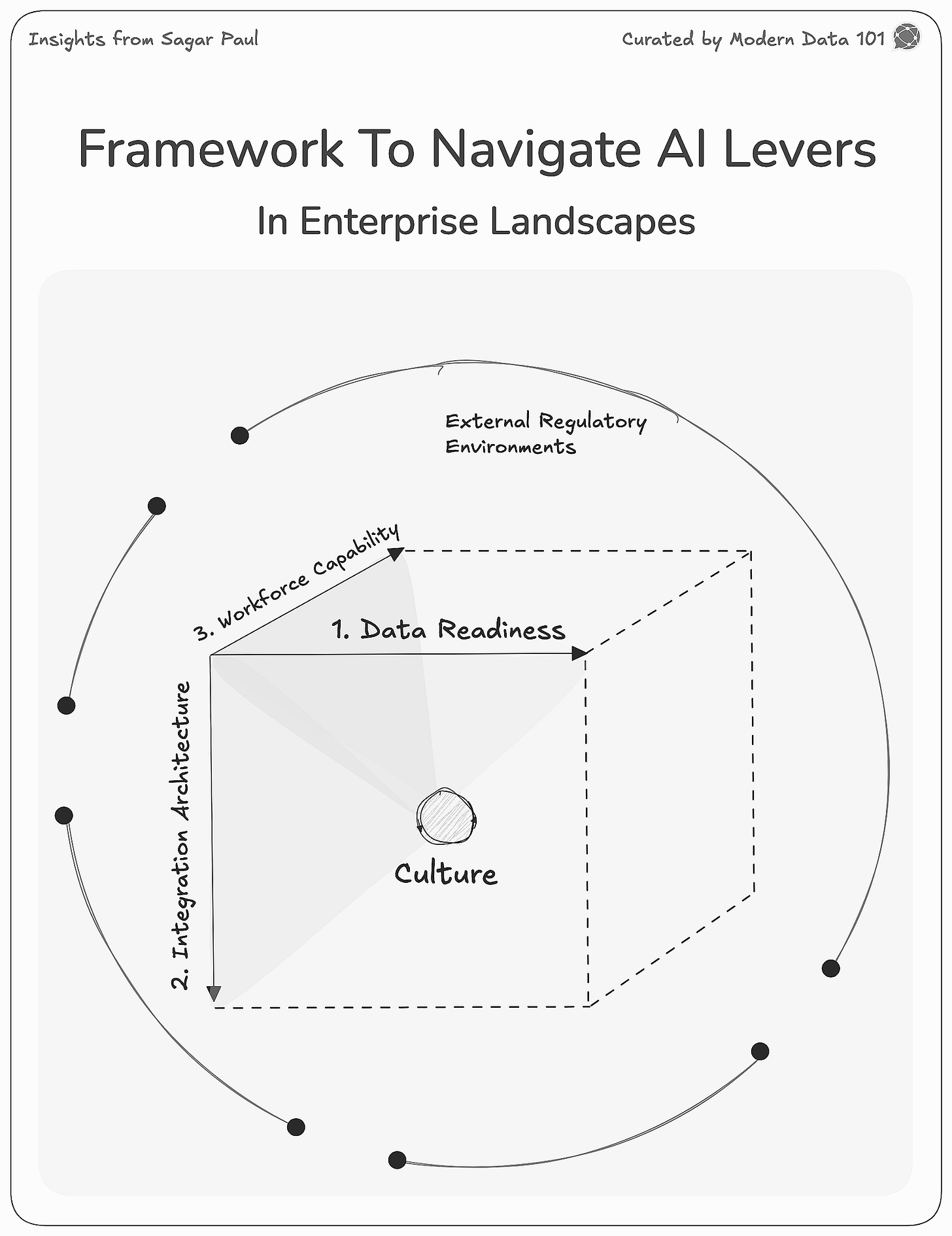

While the technology landscape appears flat, with the same models and tools available to everyone, the levers that determine enterprise success are remarkably uneven.

Data Readiness

Data readiness is the primary lever. Organizations with centralized, well-governed, high-quality data can move from experimentation to production in months. Those with fragmented, siloed, poorly documented data spend years just preparing the foundation. This is not a technology problem but an organizational and governance problem. But it determines everything that follows.

Integration Architecture

Integration architecture is the second lever. AI models are only as useful as the systems they connect to. If your customer service AI cannot access order history, inventory status, and shipping information in real time, it cannot actually solve customer problems. The enterprises that built modern API-driven architectures, often for reasons having nothing to do with AI, now find themselves with a structural advantage. Those still running on monolithic legacy systems face years of re-platforming before AI can deliver meaningful value.

Workforce Capability

Workforce capability is the third lever. The wheelwright was an essential craftsperson in every settlement, maintaining and repairing the technology that enabled commerce and agriculture. AI is creating analogous roles: prompt engineers, ML operations specialists, AI ethics reviewers, and fine-tuning experts. Organizations that develop this internal capability, either through hiring or training, will iterate faster and depend less on external vendors. Those who outsource everything will find themselves perpetually behind.

Culture

Culture is the more hidden lever. Some organizations embrace experimentation while others punish failure. Some trust algorithms while others demand human approval for every decision. Some see technology as a strategic asset while others see it as a cost center. These cultural orientations, often set decades ago by founders or industry norms, now determine how quickly an enterprise can move. Changing culture is possible but slow, often slower than changing technology.

Regulatory Environment

Regulatory environment is the external limit. No enterprise operates in isolation. Financial services firms must comply with model risk management requirements. Healthcare organizations must navigate FDA clearances. Government contractors face procurement rules that were written for a different era. These constraints are not insurmountable, but they determine the pace of adoption regardless of internal readiness.

Time stood by, until it didn’t

One divergence from the historical parallel is worth noting: wheels took centuries to spread across civilizations. AI is propagating in years.

This compressed timeline changes everything.

When the wheel spread slowly, societies had generations to adapt. New occupations emerged gradually. Road networks expanded incrementally. Social norms evolved to accommodate wheeled transport without sudden disruption.

AI allows no such luxury. Organizations have months instead of generations to develop new capabilities. Workforces must retrain in real time. Business models that were viable a decade ago may be obsolete before current strategies fully execute.

The enterprises that thrive will be those capable of learning and adapting at a pace that would have been unthinkable in prior technological revolutions.

This is not a comfortable message. It creates pressure, anxiety, and a sense that falling behind, even briefly, may be irrecoverable. But discomfort is not a reason to ignore reality. The timeline is what it is.

The View from the Train

As my fellow traveler rolled his bags off the Amtrak and toward his international flight, I wondered what he made of our brief exchange. He had spent a career in low probability of intercept, technologies designed to avoid detection. Perhaps there was a lesson there too: the most consequential technologies are often the ones you don’t see coming until they have already changed everything.

The wheel, after all, seems obvious in retrospect. We look at it now and cannot imagine why it took so long to invent. But for millennia, humans moved enormous stones, built pyramids, and conducted agriculture without it. The conceptual leap was not obvious at all.

Future generations may view our current AI debates with the same puzzlement. They will wonder why it took so long to apply these systems to problems that, in retrospect, were obviously suited to them. They will struggle to understand why some organizations resisted while others leapt ahead.

The challenge is that we cannot yet see which applications will feel inevitable in retrospect. We are living through the transition, not studying it from the safe distance of history.

What we can do is learn from the patterns. The enabling infrastructure matters more than the technology itself. Adoption follows unexpected paths. Late arrival does not mean less importance. Resistance comes from entrenched interests. Geographic and cultural factors shape deployment.

And above all: the wheel works fine. The question is whether you have proper axles and roads.

Author Connect 🤝🏻

Discuss shared technologies and ideas by connecting with our Authors or directly dropping us queries on community@moderndata101.com

Connect with Sagar on LinkedIn 🤝🏻

MD101 Support ☎️

If you have any queries about the piece, feel free to connect with the author(s). Or feel free to connect with the MD101 team directly at community@moderndata101.com 🧡

Contribute Your Voice

Join one of the most diverse and forward-thinking data communities. With 60+ authors spanning data architects, tech founders, strategists, consultants, product managers, SMEs, and industry leaders, our collective voice shapes how the world understands modern data.

Modern Data 101 is read across all 50 U.S. states and reaches readers in 135+ countries, giving every contribution a truly global footprint. We’re excited to learn more about you and explore how your expertise can help push the conversation forward. Let’s get started.