Reflecting the Language Instinct in Machines

Feasibility, Atomic structures of language, Template-matching algorithms, and Designing precision of responses for business deployments

Language, they say, is an instinct instead of a learned skill. There’s a whole book on it if you’re interested. Essentially, the idea is that while language is a wrapper, the base instinct is the need to communicate. Initially, for evolutionary reasons (humans survived because of communicating survival strategies), later, to also simply express for the sake of beauty and art.

Now that we have such huge advancements in the field of language, where academia and technology have joined hands to unify the limits of ontology, semantics, and communication, we must understand the base instinct of this capability to really excel.

What is the Base Instinct of Language

Need to unify with other seemingly isolated entities. Humans have separate consciousnesses; how must they meet, even if at a shallow level? Through communication, which is interaction. We call these interoperable exchanges ‘discussions,’ ‘brainstorming,’ ‘meetings,’ and the like.

What about entities that haven’t developed the language wrapper? The wilderness hosts countless such beings. Everything, including plants, trees, and animals of the wild. However, they too share the common base instinct: to interact. Interaction is one of the foundational keys of survival, even in civil societies. The moment there’s even a hint of it being taken away, it’s a dystopia.

Trees are known to interact through roots, scent, animals. In one particular adventure, I came across the idea of the “wood wide web:” a network so grand that it could easily beat any latest technology. These are evolutionary results of entities who have existed since long before us and instead of developing language as wrapper on the base instinct of interoperability, they went with other means.

The revelation of the Wood Wide Web’s existence, and the increased understanding of its functions, raises big questions—about where species begin and end; about whether a forest might be better imagined as a single superorganism, rather than a grouping of independent individualistic ones. ~ BBC News, How trees secretly talk to each other

Language as a Wrapper

It’s important to understand that language forms itself around the evolutionary need to unify, and different species have evolved with different inherent wrappers that enable this transaction or connection. So while language may not be the only means, it is one of the most important mechanisms humans have adopted to build civilisations and climb on top of the food chain.

The proof of language being ingrained in our systems, just one level above the base instinct, is the strange observation noted by Steven Pinker in his book. He points out that even children who have not been exposed to language models develop the ability to use structured language and grammar. As if it was another limb to be grown inherently.

And the reason children invent language even with no model, e.g. Nicaraguan Sign Language, is that evolution wired the human brain with a specialised “language organ” that automatically constructs grammatical structure from whatever signals it receives. Calling it general pattern recognition would be oversimplifying and inaccurate. It’s a species-specific, domain-specific neural specialisation.

For most of human prehistory, communication improved cooperation, cooperation improved survival, and survival improved reproduction. Groups that communicated better out-survived those that didn’t. That pressure was immense and lasted thousands of generations.

The result was a biological specialisation for creating grammar, neural circuits that expect hierarchical rules, instincts for building compositional meaning, and expectations about phonology, syntax, word classes. Children don’t copy grammar. They infer it, generate it, and standardise it.

Translating Instinct to Technology

Machines, unlike humans, do not come equipped with instincts. They have no evolutionary pressure, no biological need to unify, no cognitive compulsion to derive meaning. A child deprived of linguistic input will still invent grammar. A machine deprived of data will simply remain blank.

So when we ask whether a machine can “understand” language, the answer is almost always metaphorical. Machines don’t understand but approximate. They mimic the structures that our own instincts generate effortlessly.

But this actually reveals something profound:

If we want machines to operate meaningfully in the linguistic world we built, we must teach them the patterns that our brains generate instinctively.

Humans do not learn grammar from scratch and instead converge onto the same handful of structural patterns because evolution wired us to. Machines, by contrast, have no such wiring, but they can learn the shapes of our linguistic intent.

And this is where the world of query systems becomes fascinating.

The Atomic Shapes of Language

When an enterprise user asks an LLM, “How many shipments were delayed last quarter?” “Which vendors exceed their credit-risk threshold?” “List customers with declining month-over-month usage,”

…what appears to be “understanding” is actually the machine recognising a query-structure that maps to one of a small number of underlying patterns. This is precisely what this paper on “A Hereditary Attentive Template-based Approach for Complex Knowledge Base Question Answering Systems” talks about.

It stresses templates and multi-hop question answering patterns. We’ll later see how this also solves the incapacity of single-model LLMs to solve these complex questions. LLMs project responses, but more often than not, the responses are inaccurate or hallucinations.

Inaccurate response-mapping delivered through good frames may be a passable test case in B2C models where the mass is using LLMs for majorly low-impact use cases. But this is not applicable in serious business setups where accuracy is the cost of entry.

Humans appear to ask millions of different questions, but structurally, they cluster into atomic shapes and about more recognisable template families. This is not a coincidence but the instinctual essence of human language showing up inside tech systems.

Even when we ask naturally (with all our metaphors and ambiguity), the majority of underlying intent almost always takes one of these few grammatical forms:

Tell me an attribute

Find me something via a chain of relationships

Select entities satisfying a condition

Check if something is true

Count or aggregate

List or rank things

Structures that Capture the Essence of Human Curiosity

The reason these shapes work is the same reason why children, even without linguistic models, converge toward grammar:

Because these are the minimal cognitive patterns necessary

for humans to reason about the world.

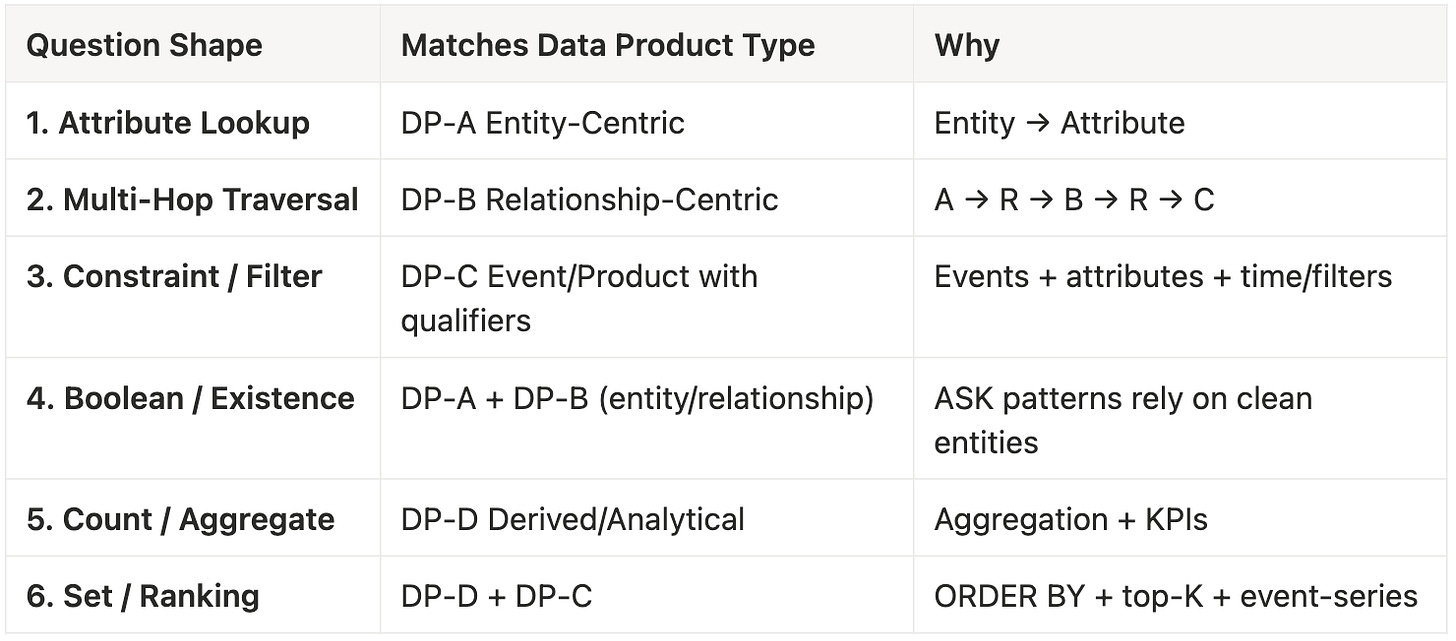

Let’s map them:

Simple Attribute Retrieval: The instinct to name, identify, describe. The “what is this?” impulse that even toddlers express.

Multi-Hop Traversal: The instinct to connect the dots. A → B → C reasoning make the basics of storytelling, memory, causality, and explanation.

Constraint / Filter Questions: The instinct to choose between options. Filtering is foundational to decision-making and survival.

Boolean Questions: The instinct to check truth. “Is this safe?” “Is this food?” “Is this friend?” Binary evaluation is ancient and biologically essential.

Count / Aggregate Questions: The instinct to measure and evaluate scale. Quantity, magnitude, comparison, all critical for resource and risk assessment.

Set / List / Ranking Questions: The instinct to survey, categorise, and prioritise.

This is how humans navigate complexity with the cognitive primitives of how human beings interrogate reality.

The deeper reasoning: Why is template classification necessary for Complex Queries

Excerpt…

*The reinvention of the Dijkstra algorithm is worth noting for all system designers and managers. It’s the first real improvement in almost 70 years for deterministic shortest-path algorithms, rewriting a “final word” in computer science.

At the risk of oversimplifying, we’ll say that it turns out the new improvement is an application of an even older problem-solving approach from the 17th Century:

Breaking down complex problems into smaller, independent units and solving each to tackle higher-order complex solutions. This approach was formalised and came to be known as deductive reasoning.

In the new Dijkstra, instead of one pile where we keep re-sorting, the researchers built something like a set of buckets or groups. Breaking down into Smaller Problems: E.g., locations aren’t all dumped into one big pile that needs sorting. They’re grouped into “zones” or “layers” based on how far they are.

When you explore, you don’t need to shuffle the entire pile. You go to the shelf that holds the next nearest point and grab from there. They replaced decades of “re-sorting” with a simpler and more brilliant “bucketing” technique.*

The same technique applies to our atomic query templates. Templates as buckets.

Similar to the divide and conquer problem, breaking an Natural Language Query into a list of intermediate representations is possible. However, the use of semantic parsing alone on a complex question can be computationally expensive due to the number of operations that must be performed to find the structure that answers a question. Template-matching can perform the semantic parsing process…. ~Excerpt

Template-matching → Agent Dispatch

Establishing the Need for Agents

Knowledge Base Question Answering systems need to deal with different kinds of questions. We can divide them into two groups: simple and complex questions.

Simple questions are those that contain direct answers and only direct entities that need to be detected to answer a question.

Complex questions need more information than the explicit features that can be extracted from simple questions.

-Excerpt from research

Singular model LLMs can only simulate responses for multi-hops or complex queries, which require creating or joining different databases. This is why many of these interfaces, including ChatGPT, have started using agents behind the scenes (the “thinking…” models), or a string of prompts self-generated from the origin.

In business, an error or untrustworthy outcome could lead to a real impact on customer experience and dollars. And more often than not, the queries in business setups ARE ALWAYS complex, requiring multiple joins behind the scenes or requiring temporary views to connect the right dots. And mind you, these reference points (tables, views, meta) need to be qualitatively sound.

E.g.: Which customers with declining MRR also increased support ticket volume in Q3?

Imagine speaking like this to your system and not just getting a simulated hallucination, but real usable numbers along with quality reports. If we classified this complex query through our templates,

Primary Template: Constraint / Filter

Secondary Template: Set / List

Internal Sub-Structure: Multi-Hop Traversal

What Powers Response Quality, and How the System Accurately “Connects the Dots”

If you peel back the layers of what makes a system accurate, you find that accuracy is always the outcome of shape. The closer the shape of the question matches the shape of the knowledge, the more naturally the answer emerges. This is true for human cognition as well as algorithm structures.

1. QA Templates: Capture the Shape of Questions

No matter how domain-heavy the context or how complex the language, every question matches or nearly-matches one of the structural forms of grammar. These are the primitives (or templates) of inquiry and the shapes human minds, even adoloscents, rely on when we ask anything or feel curiousity.

2. Data Product Templates: Capture the Shape of Knowledge

On the other side of the equation is the organisation’s knowledge. When shaped through Data Products, it settles into a stable grammar (entities, events, relationships, metrics), each conforming to a pattern that can be reasoned over, navigated, and trusted.

They are templates of understanding the enterprise’s own internal grammar.

And when we say “shaped through data products,” the shaping is not forced but highly organic, based on how different teams at different hierarchies operate and communicate with each other. We’ve written about this in great detail, where we talk about “importance as a cultural metric,” and how data products converge around these culture-driven operations. This is specific to the organisation’s shape of knowledge.

As you can observe in the sequence, the products are coming up on demand, and the use case or purpose is at the forefront at all times. Read more…

3. Question-Data Shape Alignment

Something remarkable occurs when both sides, the question and the data, share the same architectural rhythm. The question approaches the system with a known structure. The data responds to a known structure.

And the reasoning engine finds a natural bridge between the two. It feels almost organic, as if the question knows where to land. This is the moment the enterprise becomes askable. Through the gentle click of compatible shapes, like Lego blocks built from the same design language.

Templates for questions (the grammar of human inquiry)

Templates for data products (the grammar of the organisation’s knowledge)

This is the semantic contract between humans’ instinctual semantics in language, processes, and culture and machines that follow structures and have dependencies on the data input.

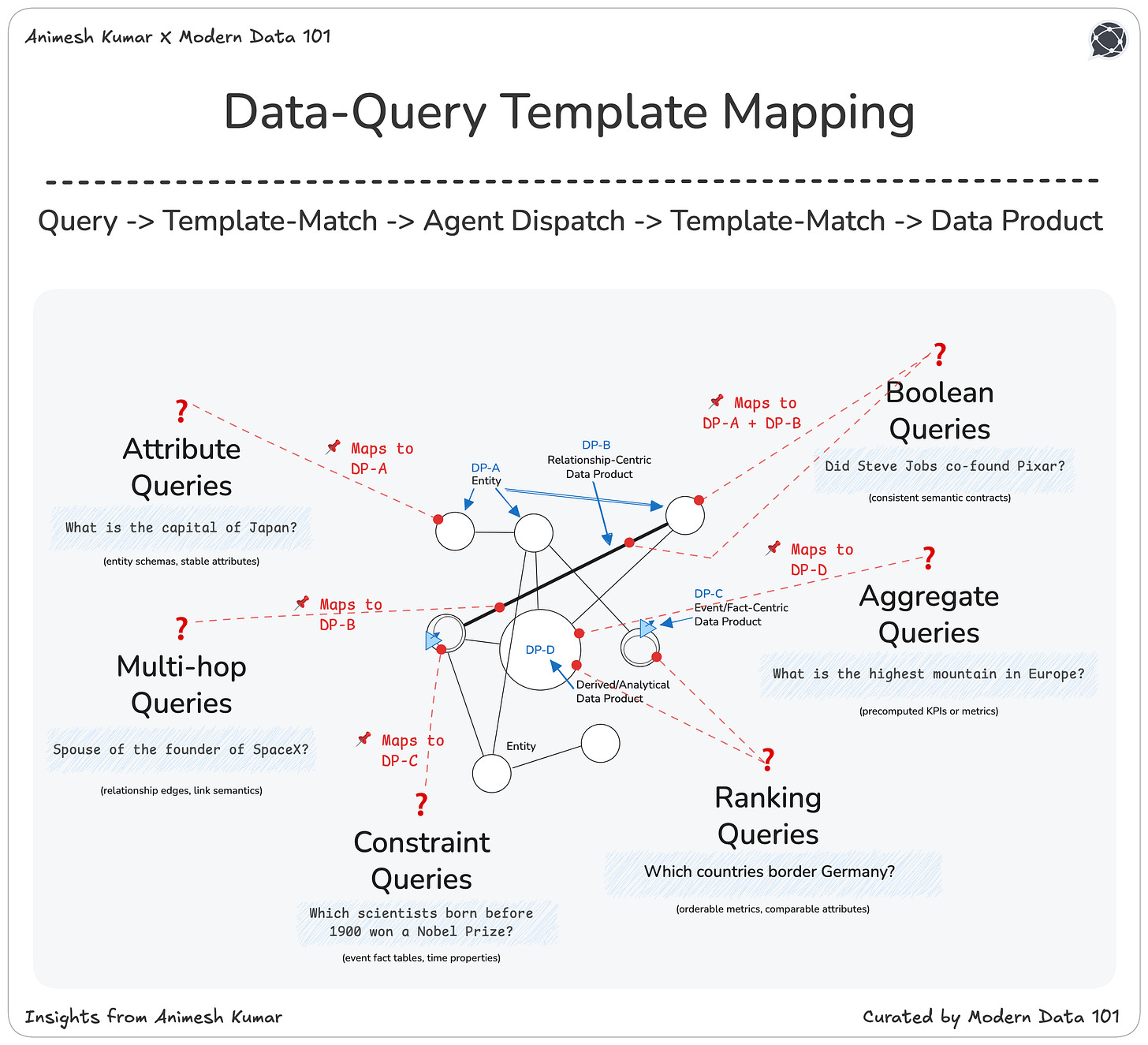

Mapping Data Product Templates To Human Query Templates

This mapping maintains high fidelity to the real knowledge landscape. For each question shape, the corresponding Data Product template provides the data structure that the question shape requires.

Data Product Templates

DP-A. Entity-Centric Data Product

The most foundational structure in any organisation is the entity itself. Each business will have no more than 9-11 entities. The “nouns” of the enterprise. These are the Customers, Products, Employees, Machines, and all other primary actors around which business logic revolves.

An entity-centric data product orbits a single core entity and captures everything that describes it: its attributes, its properties, its identifiers, and the contextual details that make it recognisable across systems. This is the purest stable template: a structured portrait of a thing or entity the business cares about.

DP-B. Relationship-Centric Data Product

The world is rarely made of isolated entities. It is made of connections. A relationship-centric data product captures these connections in their structural form: Customer → Order, Product → Supplier, Employee → Manager.

The emphasis is not on the entities but on the verb that binds them: the predicate, relationship, and reasons the link exists. This template makes the business graph navigable, allowing machines to discover meaning across nodes instead of treating data as disconnected tables.

DP-C. Event / Fact-Centric Data Product

An event-centric data product records what happened, who did it, when, and under what conditions. Transactions, sensor readings, clickstreams, all of these follow the same structural cadence: an actor, an action, a timestamp, and the contextual attributes that give the moment its meaning. This template captures the organisation’s memory, one event at a time.

DP-D. Derived / Analytical Data Product

Finally, there are the higher-order interpretations the business uses to measure itself. Derived or analytical data products don’t represent raw entities or events; they represent conclusions. KPIs, aggregates, rolling windows, segments, and scoring models are each the result of applying logic and mathematics to the underlying graph of events and entities.

Their structure revolves around definition: a metric, an aggregation method, filters, and time windows or thresholds. These products are the enterprise’s distilled insight that informs action.

How the Data-Query Template Mapping Manifests

Attribute Questions → Require Entity Schemas (DP-A)

Attribute-level queries are the simple, instinctual questions where we ask for the property of a thing. These depend entirely on the presence of a clean, well-defined entity schema. These questions lean on stability.

A customer has an industry, a product has a category, and an employee has a title. Entity-centric data products (DP-A) carry these stable attributes and descriptive properties. Without them, even the simplest “What is the X of Y?” dissolves into ambiguity.

Multi-Hop Questions → Require Relationship Edges (DP-B)

Whenever a question asks the system to travel from one concept to another, it is invoking the structure of relationships. This is the terrain of DP-B: the relationship-centric data product. Multi-hop reasoning becomes possible only when these edges exist explicitly and consistently.

The semantics of the link and the “why” behind the connection must be encoded. Without these connective metadata and context/metadata, the system cannot depend on high-quality relationships. Quality becomes trapped inside isolated entities. Quality gets trapped inside isolated entities.

Constraint and Filter Questions → Require Events and Time (DP-C)

Constraint-driven questions, particularly those involving time slices, thresholds, or conditional logic, depend on the stream of ‘facts’ of the enterprise: events. Event/fact-centric product templates, provides the actor, the action, the timestamp, and the contextual attributes that filtering requires.

When we ask, “Which customers increased ticket volume in Q3?” we are standing squarely on the foundation of the DP-C template. Time and conditions are all here.

Boolean Truth Checking → Requires Semantic Contracts (DP-A / DP-B)

Boolean questions such as “Is this true?” and “Did this happen?” depend on consistency. They require a semantic contract between what an entity is (DP-A) and how it connects to others (DP-B).

Aggregations → Require Pre-computed Metrics (DP-D)

Aggregation questions, such as counts, averages, sums, and groupings, exist in the derived layer, DP-D. This is where definitions and logic are defined into KPIs, ratios, windows, and segments. Aggregation demands clarity on what exactly is being counted, aggregated, or ranked. DP-D provides this clarity by formalising metrics that the rest of the system can trust.

Ranking → Requires Comparable Metrics (DP-D + DP-C)

Ranking and listing require both metadata on facts from DP-C (event-centric) and the interpretive capability of DP-D (aggregate). DP-C provide the fact data around event entities like sales, clicks, usage, while derived metrics make these comparable across entities or time. Top-N lists, leaderboards, and prioritisation systems become reliable responses when the metrics are comparable (connected) and verified.

Final Note

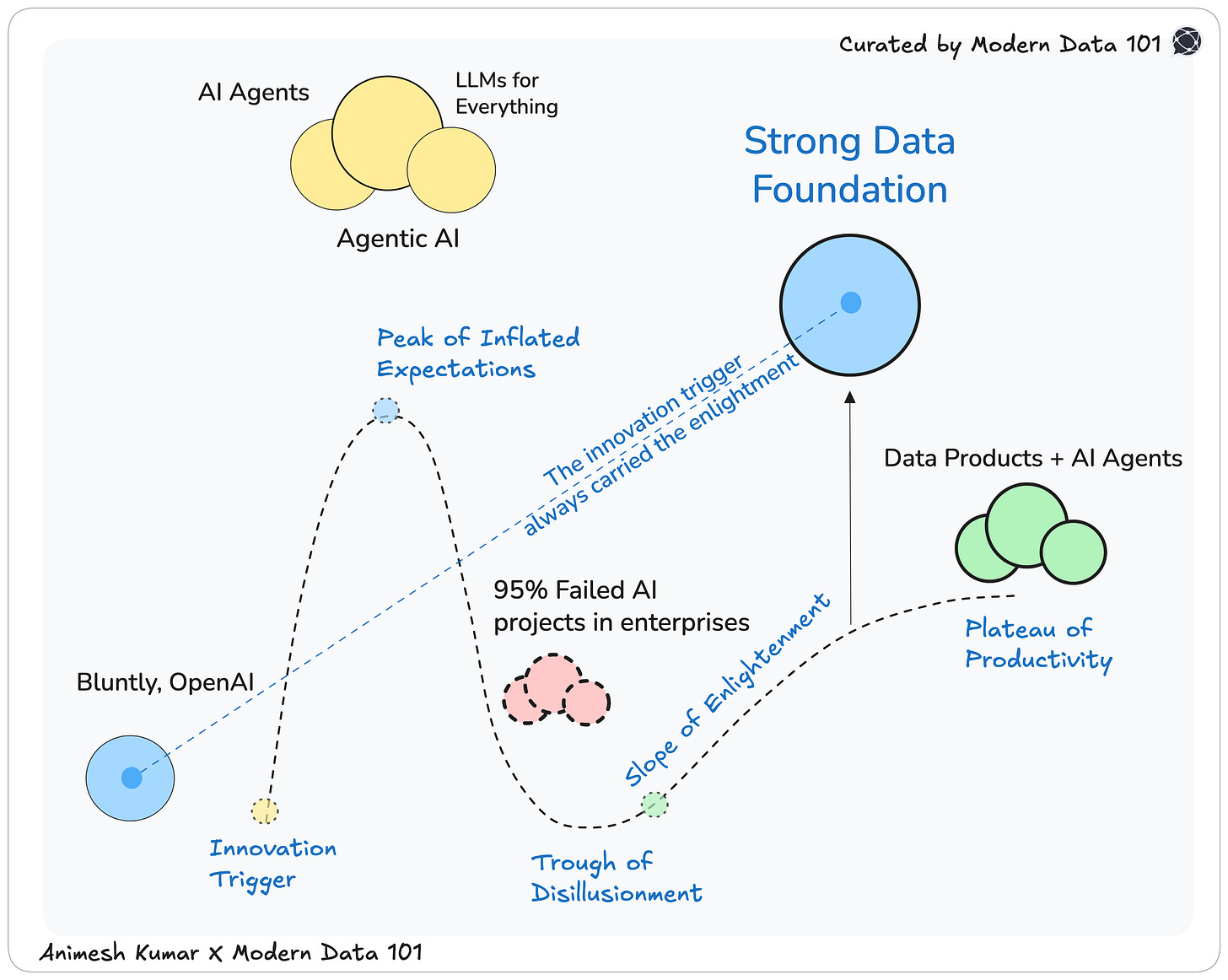

Scaling “cognitive” systems in high-stakes business environments requires a ton of work. Anybody who tells you otherwise is peddling a pipe dream.

MD101 Support ☎️

If you have any queries about the piece, feel free to connect with the author(s). Or feel free to connect with the MD101 team directly at community@moderndata101.com 🧡