Reconfiguring AI as Data Discovery Agent(s)?

Loosely coupled, tightly integrated relationships between Data Platforms and Agents that drive cultures of integrity, transparency, accountability, and trust in Agentic workforces.

“The thing that hath been, it is that which shall be; and that which is done is that which shall be done: and there is no new thing under the sun” | Ecclesiastes 1:9

For most of human history, knowledge was scarce. It had to be discovered, recorded, preserved, and transmitted with care. Today, we live in the opposite condition. Whatever we know or talk about has already been published, spoken, or written somewhere. This was true first of literature, then of history, and it became overwhelmingly true with the internet.

“All is said, we have come too late; for more than seven thousand years there have been humans, thinking” | Jean de La Bruyère

Need a recipe? It exists in some forgotten blog post, a forum thread, a video, or a scanned cookbook. Need to learn a programming language? There are countless tutorials, curricula, walkthroughs, and opinionated guides. Need a detailed breakdown of a niche concept that only a handful of people care about? Chances are, someone has already written it, explained it, argued about it, and archived it online.

The Untapped Power of Discovery

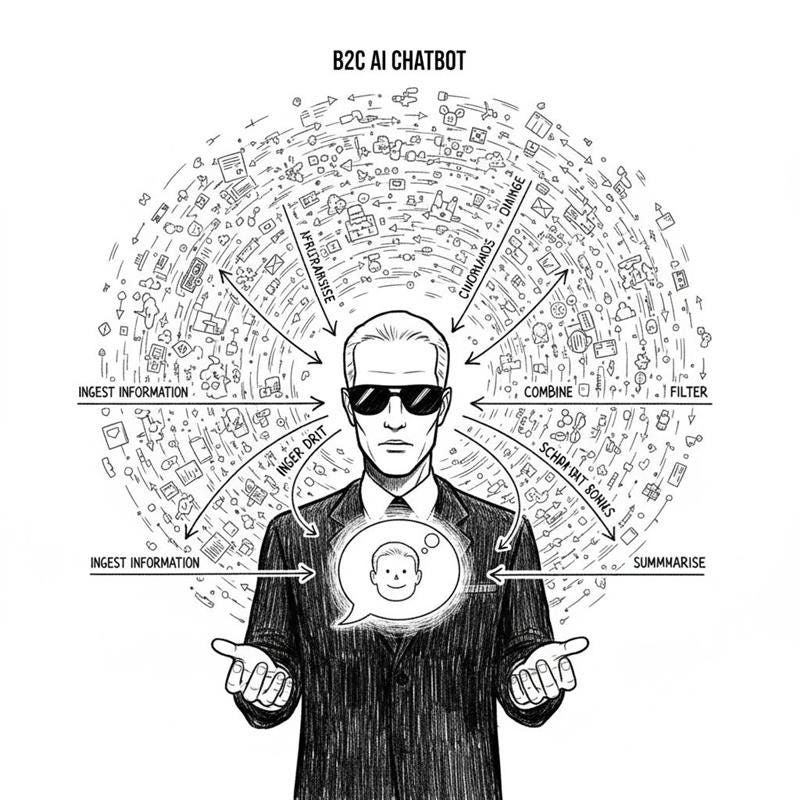

B2C AI chatbots are built to thrive in exactly this environment. At their core, they function as extraordinarily sophisticated search engines: systems that ingest the vast expanse of publicly available information and learn how to combine, filter, compress, and summarise it in a way that aligns with the user’s intent.

Their real strength is not recall alone, but intent interpretation: understanding who the user is, what they are likely trying to achieve, and how much depth or precision is required in the response.

“Everything clever has already been thought; we must only try to think it again.” | Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

These systems are remarkably good at deciding what not to search, narrowing the space of possibilities to save compute/time, and identifying similarities and patterns with almost unsettling accuracy. They do not just retrieve information, but reorganise it on demand.

And yet, we all implicitly accept that these responses come with a margin of error. Hallucinations, approximations, and confident inaccuracies are part of the bargain. In a consumer context, this is largely acceptable. The cost of being wrong is usually low. A flawed explanation, an imperfect recommendation, or a slightly incorrect summary rarely carries material consequences.

Why Untapped

But this acceptance is a product of a B2C operating lens. The moment we move into B2B environments, the tolerance for error collapses.

Business decisions are not exploratory curiosities, they compound. They affect revenue, compliance, customer trust, and operational stability. In these contexts, inaccuracies are liabilities.

While B2C use cases tend to centre around research, learning, navigation, and individual productivity, B2B use cases are fundamentally collective. They inform decisions made by teams, executed by systems, and scaled across organisations.

The question, then, is not whether AI can generate answers, but whether those answers can be trusted when the cost of being wrong is no longer personal, but organisational.

What problem are we actually solving?

Humans do not need more data. They need to know what exists, whether it can be trusted, and whether it can be used safely. Fast enough to act.

Everything else (catalogs, lineage graphs, AI copilots) is implementation detail.

The irreducible questions every data consumer asks, implicitly or explicitly:

Does this data exist?

Can I access it?

Can I trust it?

Is it relevant to my goal, right now?

What happens if I use it incorrectly (the cost of error)?

These questions are universal, regardless of whether the person asking them is an analyst, a machine learning engineer, a product leader, or an executive.

The data catalog, in its original form, emerged as an attempt to answer these questions in a static world. It documented assets, traced lineage (barely), assigned ownership, and tried to encode trust through description.

In modern systems today, AI is the new interface for answering the very same questions.

The Gap

This shift exposes a fault that most conversations conveniently avoid. An AI that merely retrieves descriptions is still operating at the surface of the problem, like any other integrated catalog.

Additionally, with hallucinations, the AI version seems to be faster, more fluent, and more confident (tools that easily rope in humans’ trust during first few interaction levels). But the AI is not “smarter” yet.

The inflexion point appears only when AI begins to reason over evidence: quality signals, usage patterns, access constraints, lineage, and risk, all grounded in the operational reality of the data platform.

So the question is no longer whether AI can talk about data. The question is whether it can reason about data in the way a careful human would.

Breaking Discovery Into Smaller Solutions

To make progress, the problem itself has to be reduced. “AI-powered data discovery” is too large, too abstract, and too flattering a phrase to be useful.

It bundles multiple distinct problems into a single label and gives the illusion of completeness without earning it. The only way to reason about it clearly is to decompose it into smaller units of atomic solvable problems.

At the highest level, the problem sounds simple: help me discover the right data for my intent, safely and confidently.

But this apparent simplicity hides a chain of judgments that must all hold true at the same time. Discovery is not a single action, but a sequence of judgements. And every weak link in that sequence disrupts trust or the data consumer experience almost completely.

Existence problem: What data assets exist?

Access problem: Am I allowed to see or use them?

Context problem: What do these assets mean?

Quality problem: Should I trust them?

Usage problem: How are they actually being used today?

Intent alignment problem: Which asset fits my goal, not just any goal?

Risk problem: What could go wrong if I use this?

Traditional data catalogs attempt to answer some of these questions, usually in isolation and usually statically. They describe, document, and point. But discovery, in its true sense, is dynamic.

An AI-driven discovery system must be able to evaluate all of these dimensions together, in real time, and in context. And context is what isolated or independent catalogs do not have access to, given the lack of knowledge, context, visibility, and granular logs operating within native data platforms of organisations.

Any catalog that promises AI-led discovery is, in most cases, working on a surface level with AI, given that it is inherently unable to reason over key ecosystem information that is not accessible to it due to tooling/regulatory/lock-in barriers.

AI is NOT the Data Catalog of the Past

Discovery is inference grounded in evidence. When AI is asked to help users navigate data without access to observable signals like quality, usage, access, change logs, it has no choice but to substitute reasoning with approximation. The output may sound coherent, even authoritative, but it is untethered from reality.

Which is most dangerous in business setups, given the AI’s ability to simulate trust is almost too frequent in one-on-one interactions with humans.

Reconfiguring AI as a discovery tool only works when the underlying platform behaves like an instrumented system.

Quality must be measurable: freshness, completeness, test health, and failure history need to exist as first-class signals.

Usage must be visible: who relies on the data, how frequently it is queried, and which workflows break if it disappears.

Access rules must be explicit and machine-readable.

And metadata itself must move beyond description, serving as something systems can reason over.

In the absence of these foundations, AI does not become smarter, but it definitely appears to be more confident. It starts to resemble a search engine that speaks fluently, stitching together partial truths and plausible narratives without accountability.

A reasoning system, by contrast, is constrained by evidence. It can explain not just what it recommends, but why and, just as importantly, when not to.

That distinction is not achieved through better prompts or larger models but earned by platforms that measure reality well enough for AI to reason about it.

Meeting in the Middle: Top-down AI × Bottom-up

Metadata Infrastructure

From the top down, AI brings intent. It understands natural language, infers personas, and adapts to goals that are often loosely articulated. This is the visible side of the system, and it is genuinely powerful. This is the part of the system most people see and often overestimate.

But intent by itself is ambiguous. Two people can ask the same question and mean entirely different things. Without grounding, intent becomes speculation.

From the bottom up, the data and context platform provides evidence. But evidence does not appear magically as “metadata.” It has to be produced.

A foundational data infrastructure must actively assess and gauge the state of the data estate. It does this by observing pipelines in motion, tracking freshness and failures, running quality checks, recording access patterns, capturing lineage as systems evolve, and enforcing policies at runtime. Metadata, in this sense, is measured instead of being written.

Measured metadata forms the bridge to reasonable AI

It translates raw operational signals into something AI can interpret: which datasets are healthy, which ones are trusted, which are widely relied upon, which are volatile, and which carry risk. It also encodes constraints like who can access what, for which purposes, and under what conditions. Without this bridge, AI has no stable reference frame. It can speak fluently, but it cannot judge.

Once this foundation exists, AI’s role changes fundamentally. It is no longer guessing relevance but evaluating. It is no longer summarising descriptions but reasoning over observed behaviour.

It can weigh intent against evidence, adapt recommendations based on persona and risk tolerance, and explain why one dataset fits a goal better than another. The quality of its answers becomes a function of the quality of the signals it consumes.

This is why meeting in the middle is not optional.

Top-down intelligence without bottom-up measurement produces hallucination: answers that sound right but are untethered from reality.

Bottom-up measurement without top-down intelligence produces complexity: truth that exists but cannot be navigated simply.

The bridge between the two is the system that makes discovery at par with current AI systems: a platform that measures reality continuously, and an AI that knows how to reason with it.

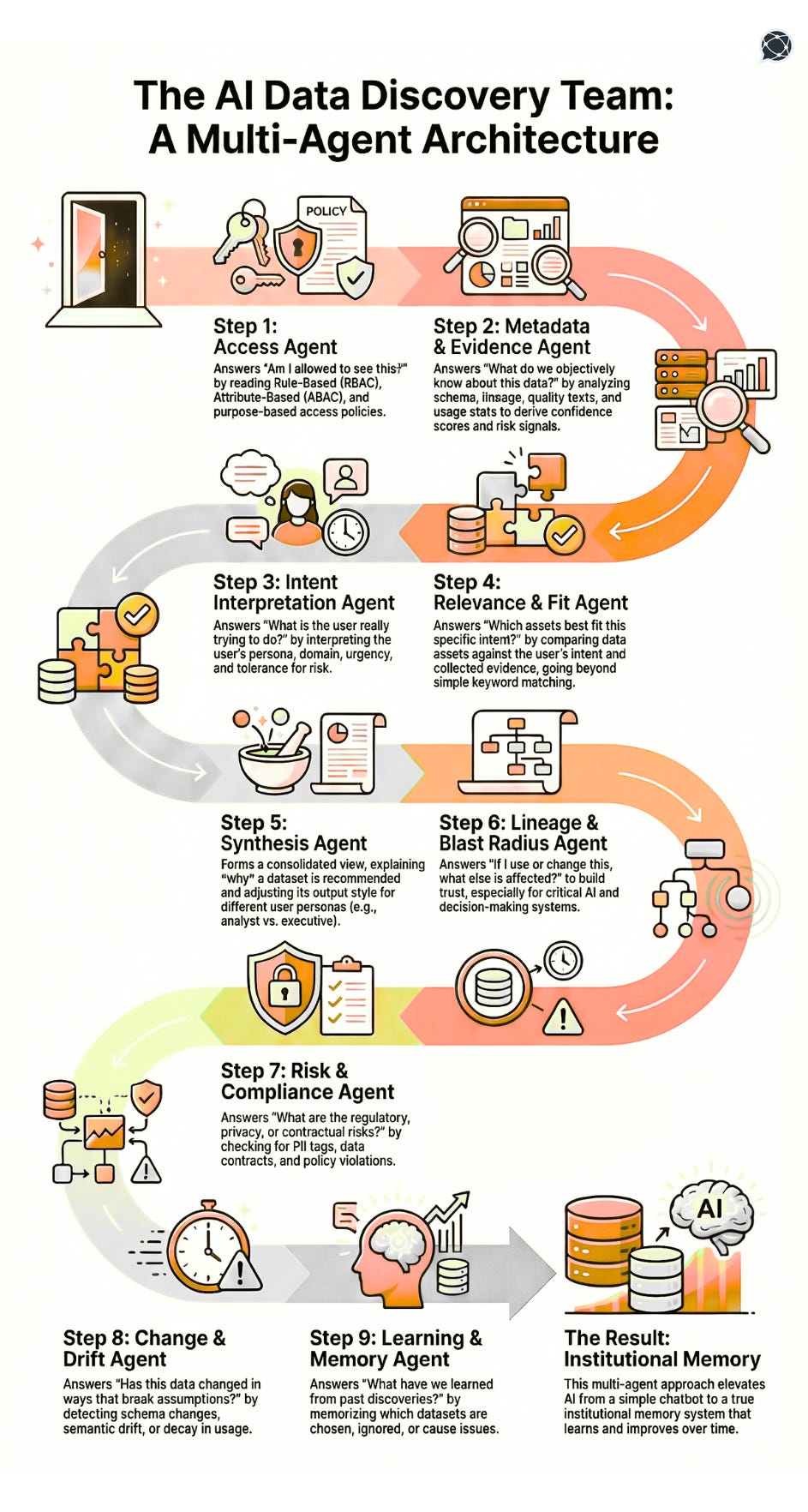

Optimising Discovery with a Chain of Agents

The most common assumption is that discovery is a single act. Ask a question, get an answer. In reality, discovery is not atomic. It is a sequence of judgments, each dependent on the previous one being correct.

A useful way to reason about AI-driven discovery, then, is not as a monolith but as a chain of agents: each responsible for a specific decision boundary.

From first principles, any discovery flow that aspires to be production-grade must be decomposed into a sequence of bounded judgments. Each judgment becomes an agent because it enforces a clean contract: specific inputs, explicit outputs, and known error surfaces.

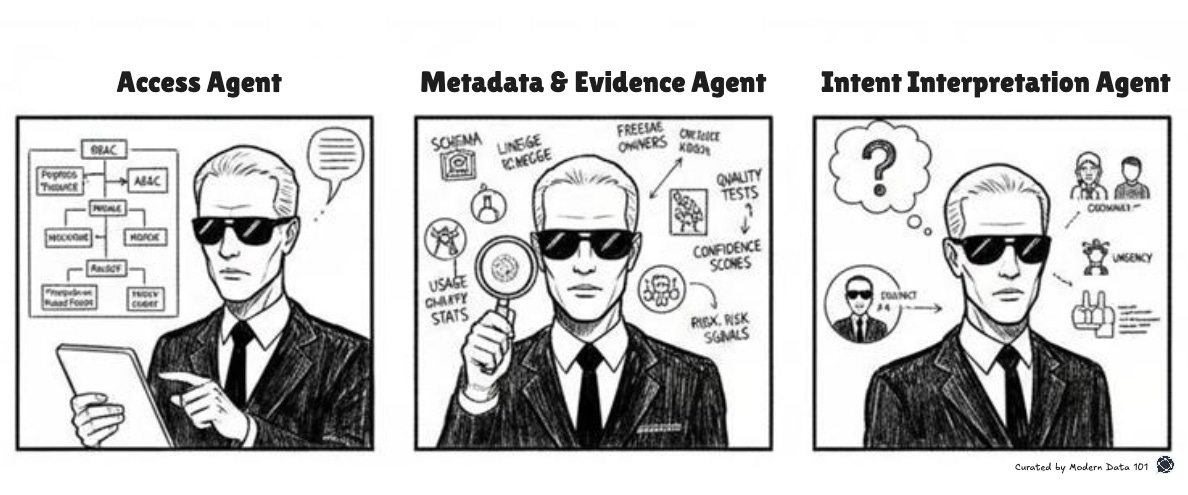

Access Agent

Enforcing hard boundaries before reasoning begins.

Intent: The Access Agent exists to terminate invalid discovery paths as early as possible. Its job is not to explain policy, but to enforce it deterministically.

Consider a user asking, “What customer revenue data can I use for churn modelling?” Before intent is interpreted or metadata is explored, the system must resolve whether the user can access raw customer-level financial data, only aggregated metrics, or nothing at all. This agent reads RBAC/ABAC rules, purpose constraints, and data contracts, and produces a filtered worldview of permissible assets.

Why is this not implicit?

If access checks are deferred or embedded inside a general reasoning step, the system reasons about assets it should never have seen. That creates both security and hallucination risk. Architecturally, access must be a gate instead of a suggestion.

Long-term system impact: Over time, discovery becomes policy-shaped by default. The system never “forgets” access rules, even when humans do.

Metadata & Evidence Agent

Separating observation from assumption.

Intent: This agent exists to answer a narrow but critical question: what can we prove about this data right now?

Take two datasets labelled “customer_orders.” One is refreshed hourly, heavily used in revenue reporting, covered by tests, and owned by finance. The other is refreshed sporadically, used only by one analyst, and fails freshness checks weekly. A human might not notice this distinction. This agent must.

It consumes schema, lineage graphs, freshness metrics, test results, failure logs, and usage telemetry to produce derived signals such as confidence, stability, and operational risk.

Why an independent agent for evidence?

Evidence evaluation is not intent-dependent. It must be consistent regardless of who asks the question. Architecturally, that makes it a reusable judgment unit.

Long-term system impact: The system stops treating metadata as documentation and starts treating it as evidence.

Intent Interpretation Agent

Resolving ambiguity.

Intent: This agent exists to resolve ambiguity in human input before any asset ranking occurs.

A question like “Show me user engagement data” is underspecified. Is this for executive reporting, product experimentation, or ML feature generation? The same words imply different correctness criteria. This agent infers persona, domain context, urgency, and acceptable risk based on the user’s role, historical behaviour, and session context.

Why can this not be merged with retrieval?

Intent is not a property of data, but a property of the user. Mixing intent inference with data reasoning creates circular logic and unstable outputs.

Long-term system impact: Discovery becomes outcome-aligned rather than query-aligned. The system always optimises for usefulness over literal matches.

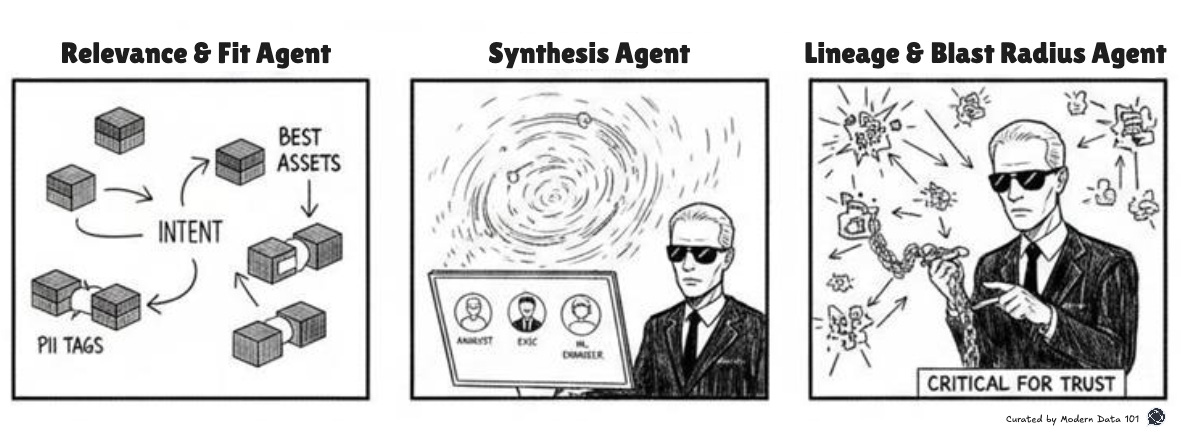

Relevance & Fit Agent

Evaluating suitability.

Intent: This agent answers the actual selection question: which asset best fits this intent under current constraints?

For financial forecasting, a slower but audited dataset may be preferred. For exploratory analysis, a fresher but noisier dataset might be superior. This agent compares evidence (quality, usage, stability) against intent-derived requirements.

Why make this an independent agent?

Most systems implicitly equate relevance with description quality or usage frequency. Making this an agent forces relevance criteria to be articulated and inspected instead of being rule-driven.

Long-term system impact: Data selection becomes defensible. When decisions are questioned, the system can explain tradeoffs.

Synthesis Agent

Assembling judgment into explanation

Intent: This agent exists to convert a multi-step reasoning process into a human-comprehensible outcome.

Rather than saying “Use dataset X,” it explains: Dataset X is recommended because it is refreshed daily, widely used in finance workflows, passes quality checks, and aligns with your reporting intent. Dataset Y was excluded due to freshness and access constraints.

Without synthesis, multi-agent systems feel arbitrary. Explanation and reasoning evidence convert human doubt into trust.

Long-term system impact: Discovery decisions become auditable and teachable, reducing reliance on tribal knowledge.

Lineage & Blast Radius Agent

Reasoning about consequences.

Intent: This agent evaluates downstream impact before action is taken.

If a dataset feeds a revenue dashboard, a pricing model, and an external report, using it for experimentation carries risk. This agent traverses lineage to surface those dependencies explicitly.

Long-term system impact: The organisation develops systemic awareness. Changes stop being local accidents and start being intentional actions, which often turn out to be rewarding to humans.

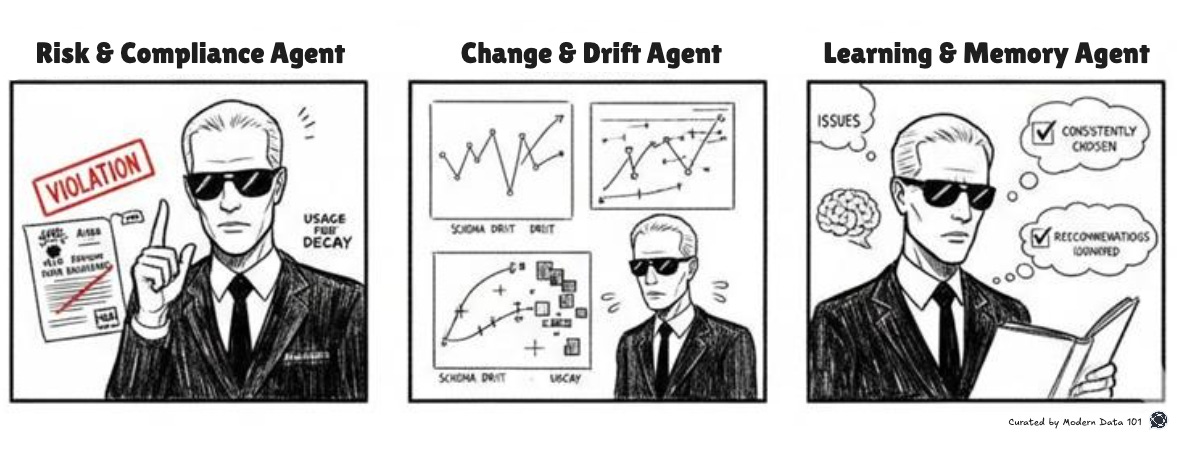

Risk & Compliance Agent

Making constraints first-class

Intent: This agent ensures that legal and contractual realities shape discovery. Reactive governance is way in the past for this agent.

A dataset may be technically perfect but unusable for a given purpose due to consent or contractual limits. This agent reads PII classifications, consent scopes, and historical violations to constrain discovery paths.

Long-term system impact: Risk evaluation shifts from post-hoc governance to pre-decision design.

Change & Drift Agent

Invalidating stale trust.

Intent: This agent asks whether past assumptions still hold.

If schema changes invalidate a downstream model or usage drops sharply, this agent dials down confidence scores/ranks automatically.

Long-term system impact: System resists fossilisation.

Learning & Memory Agent

Institutionalising experience.

Intent: This agent captures outcomes to improve future discovery.

If a dataset is repeatedly selected and later leads to incidents, the system learns to penalise it. If recommendations are ignored, the system adjusts relevance.

Long-term impact: AI becomes organisational memory.

Overview of Our Recommended Discovery Agents

Note that the sequence in the image follows the order in which they’re described. While some of the agents are sequential, some operate in parallel or interchange data both ways.

Author Connect 🤝🏻

Discuss shared technologies and ideas by connecting with our Authors or directly dropping us queries on community@moderndata101.com

Find me on LinkedIn 🙌🏻

MD101 Support ☎️

If you have any queries about the piece, feel free to connect with the author(s). Or feel free to connect with the MD101 team directly at community@moderndata101.com 🧡