Closing the Architecture Gap Between FAANG and Enterprises | Case: Meta | Part 2.2

Not how Meta built it, but how Meta thinks: the missing link in enterprise data architecture, deploying data developer platforms, and mapping outcomes.

…continued from Part 2.1: How Meta Turns Compliance into Innovation.

This part addresses:

1. Areas of mismatch: How legacy or enterprise data architectures fall short of Meta’s Privacy Aware Infrastructure

2. Inspiring Meta’s business-aligned outcomes instead of trying to replicate their state-of-the-art data architectures that have been chiselled for decades

The systems we admire at Meta, Google, or Netflix are physical artefacts of an organisation’s design philosophy: the accumulated expression of how these organisations think about data, software, responsibility, and scale.

What we see on the outside is only the final shape of decades of internal reasoning.

Enterprises make the mistake of following in the footsteps of these advanced data- and tech-first orgs to replicate the same business shape. They adopt the warehouse-lakehouse-governance stack, the “state-of-the-art” privacy tooling, pick as-is catalogs and create the same views, probably replicate mesh-inspired domains, and believe they have reconstructed a high-functioning data infrastructure. But replicating the visible layers without reflecting the enterprise’s operating logic is a high-cost mirage. The tools may look contemporary, but the underlying behaviour and how they interact with each other and data entities still reflect legacy constraints.

This is why so many transformations end up feeling hollow. The architecture appears modern when diagrammed, yet it behaves exactly like the old one when work flows through it.

The problem is not that enterprises are missing a particular tool or framework. The problem is that they are copying an artefact without understanding its cause. This piece exists in the hope of highlighting that cause and shifting the conversation from replication to reasoning so that organisations stop inheriting shapes and start adopting first principles.

If you’ve not followed along our trail, this article is part of a series where we break down state-of-the-art architectures, map gaps and compare with legacy frames, shine light on disillusionment trails, and show plausible alternatives to design business outcomes without the infrastructure lift-and-shift.

📝 Previous parts in series

Where Enterprise Infrastructure Falls Short: The Five Structural Mismatches

In this article, we are diving into the specifics of Meta’s data architecture to map the gaps between core enterprise architectures and state-of-the-art designs. You may read about Meta’s architecture preview here ↗️.

This is a first-principles breakdown of the areas where legacy architectures diverge from Meta’s Privacy-Aware Infrastructure (PAI). But first, a lookback on Meta’s PAI Data Infrastructure:

Mismatch #1: Governance as Afterthought vs Governance as Primitive

Enterprises still treat governance as something that must be added later: a layer(!) of rules, committees, and approvals that tries to shape behaviour from the outside. Meta inverts this entirely: governance is not a wrapper but the foundational design of their data platform.

Governance is encoded directly into schemas, annotations, and runtime IFC enforcement. Enterprises try to control behaviour, while Meta defines it. Governance kicks in from the exact point where data passes through the very first touchpoint in Meta’s data ecosystem.

Mismatch #2: Annotation Poverty vs Annotation Wealth

Most enterprises operate in a desert of annotation. Data arrives raw, unlabelled, and semantically ambiguous, forcing downstream teams to reverse-engineer meaning. This becomes a guesswork exercise that inevitably produces inconsistencies and compliance gaps. Meta takes the opposite path: annotate as early as possible, as consistently as possible, and as universally as possible.

By giving every asset a purpose label from birth, Meta creates the semantic spine that allows enforcement, lineage reasoning, discovery automation, and privacy guarantees to scale. Enterprises never achieve this semantic intelligence because they start too late.

Mismatch #3: Tool Sprawl vs Platform Primitives

Enterprises accumulate tools and almost hoard them. This is often because there are multiple decision points, and each point believes in solving a narrow visibility problem. Or there’s frequent change of decision makers, which leads to biases on tools and tech.

Meta builds something far more foundational and, you may not believe, but far simpler (design-wise): independent units of action, independent zones of action. Annotations (independent labelling that provides purpose), policy zones (localised, SDKs, enforcement runtimes, and automated discovery shape behaviour without relying on tool-of-the-week additions.

Mismatch #4: Periodic Governance vs Continuous Enforcement

Enterprise governance is episodic. Quarterly reviews, spreadsheet-driven audits, and manual reconciliations are some examples. Like tasks following up to meet compliance checks. Meta replaces this with governance in runtime, and instead of periodically inspecting the system, Meta’s architecture continuously constrains it. Enterprises watch after the fact while Meta shapes as it happens.

Mismatch #5: Organisation as Obstacle vs Organisation as Design

Enterprises treat organisation (organising assets) like taxonomy, metadata, semantics, classification, etc., as documentation, as tools for compliance instead of clarity. Meta treats organisation as a design pattern, an engineering discipline that underpins every stage of data production and consumption. This is why Meta’s infrastructure maintains legibility at scale while enterprises drown in ambiguity. Clarity is not a project; it is a practice, and Meta practices it relentlessly.

The Temptation: Trying to Replicate Meta’s State Instead of Meta’s Intention

Enterprise leaders often attempt to recreate state-of-the-art data infrastructures and end up referring to the visible layers of the inspiration without understanding the intent that produced them. They end up doing the following:

Deploy catalogs but don’t annotate at scale

Install lineage but don’t unify purpose

Add privacy layers but don’t run continuous enforcements

Experiment with ML discovery but don’t build the semantic spine these systems require.

The result is predictably high spend, low impact, and architectures that look sophisticated but behave exactly as before. Meta’s infrastructure is not a template to replicate but the natural consequence of a philosophy that prioritises purpose, semantics, and organisation at the very foundation.

This prioritisation would look different and manifest differently for different organisations.

Trying to copy the state without adopting the intention guarantees failure.

The Path Forward: Don’t Copy Meta. Inspire Their Outcomes.

Enterprises don’t truly need Meta’s infrastructure, but they definitely aspire to the outcomes that such infrastructures enable. Trustworthy data, safe AI.

One layer deep, these imply unambiguous purpose boundaries, governance that can be automated instead of enforced by committees, faster developer velocity, and compliance as a side-effect of good design.

None of these outcomes requires Meta’s decade-long investment or its bespoke internal systems. They require adopting the same philosophical posture: encode intent early, treat semantics as engineering, and let governance be inherent in the platform rather than at the edges of it.

This is precisely where the Data Developer Platform (DDP) standard enters the picture.

Data Developer Platforms: A Meta-Like Architecture for Everyone Else

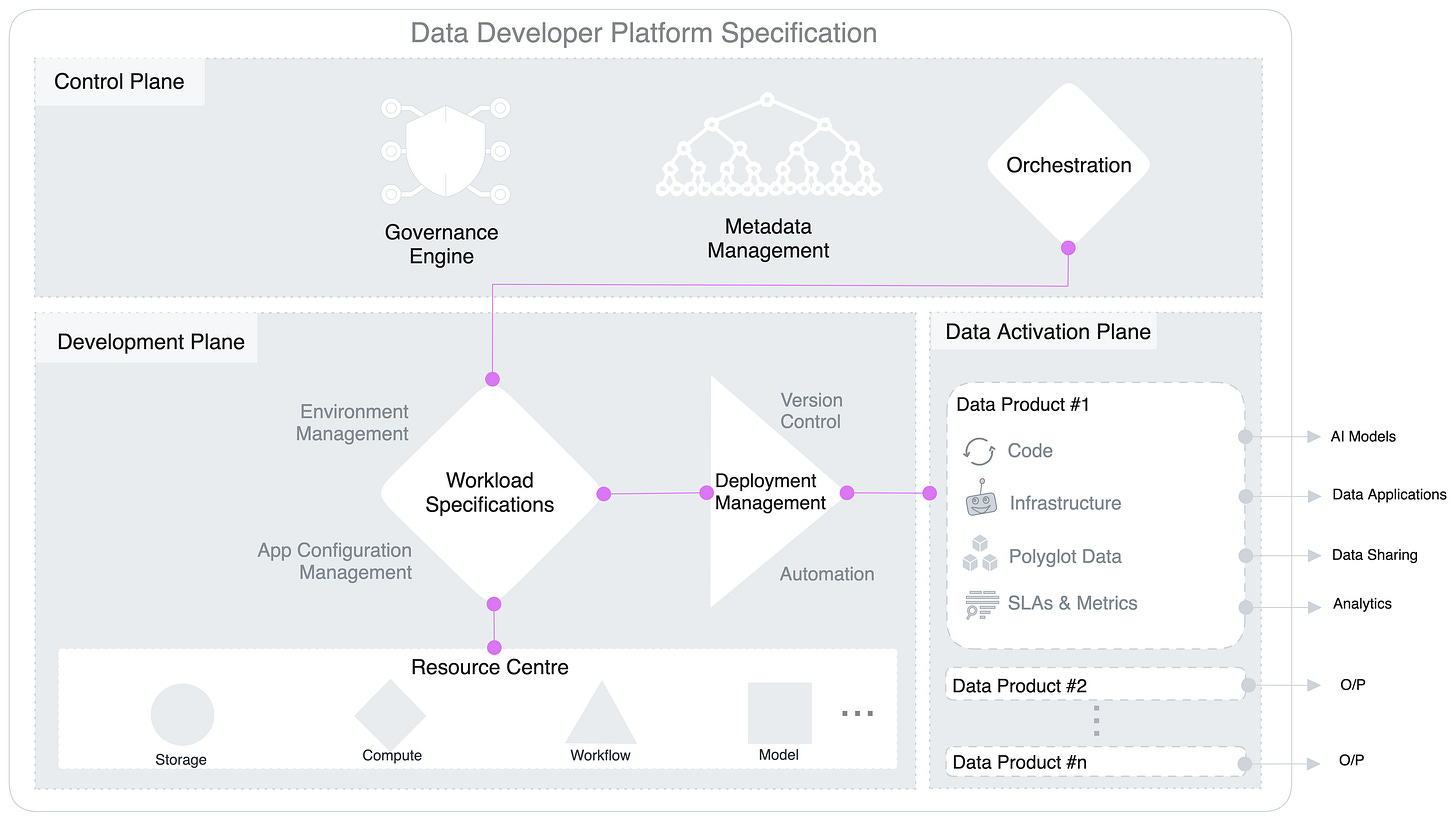

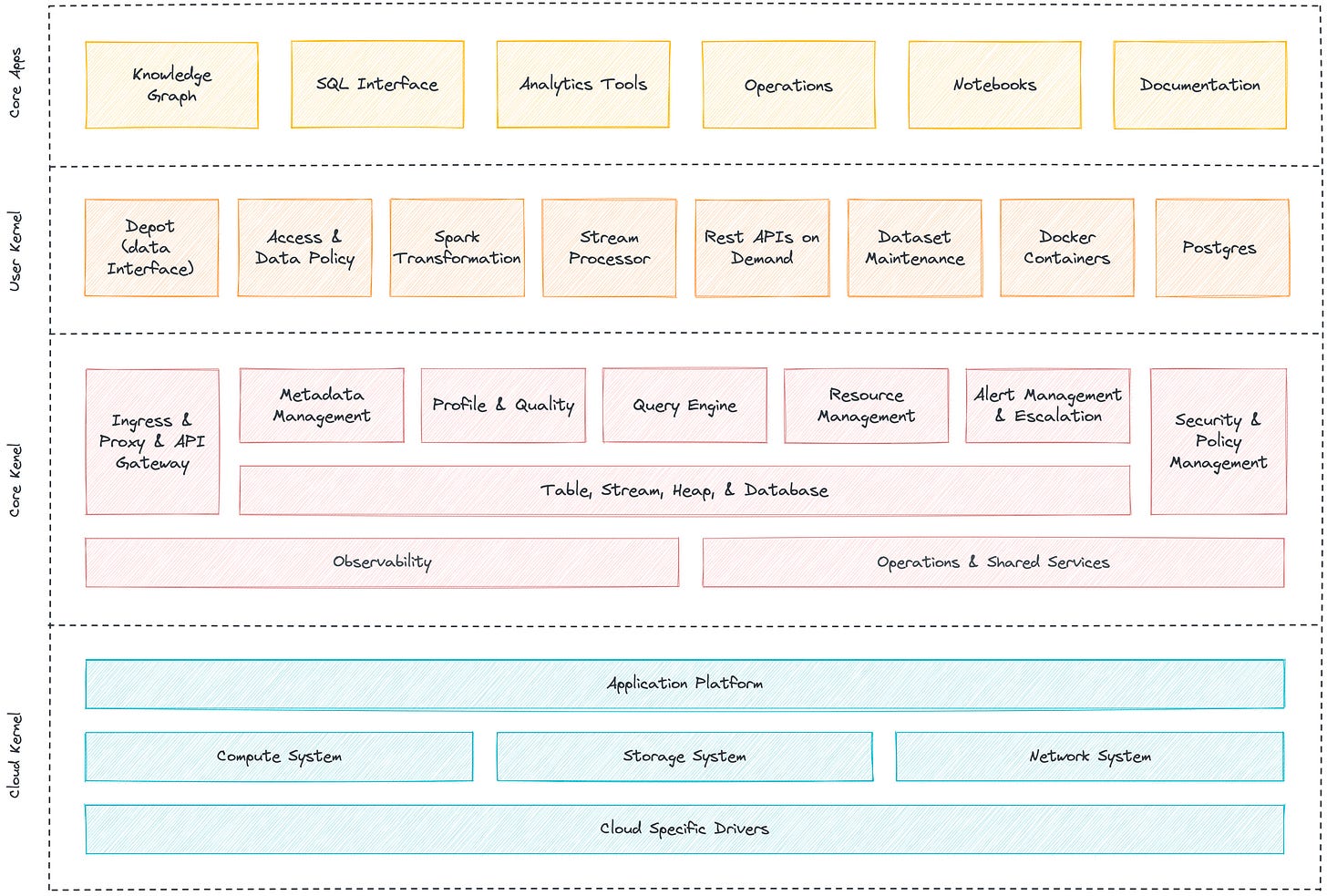

Unlike Meta’s 10–15 years of internal evolution, DDPs give enterprises a composable, primitive-based system to express the same principles through configurable patterns.

What is a Data Developer Platform?

A Data Developer Platform is not another tool in the enterprise toolbox. It is the foundational interface on which an organisation’s entire data ecosystem behaviour is shaped. A DDP provides primitives (think of it as similar to LEGO blocks): the core building blocks from which teams can design architectures that reflect their organisation’s goals, semantics, and intended behaviours.

It rejects the industry’s tool-first impulse and instead starts with purpose: what the organisation is trying to achieve, what meaning its data carries, and how that meaning should govern every flow, transformation, and interaction.

A DDP is semantic-first rather than pipeline-first, enabling systems that understand intent. DDP defines a composable data platform, allowing each company to build/customise its own design patterns, specific to the organisation’s operating language. Without inheriting the unnecessary complexity of someone else’s architecture.

Core characteristics:

Goal-first, not tool-first

Semantic-first, not pipeline-first

Composable primitives, not rigid products

Purpose-aware, not dataset-aware

Workflow-oriented, not dashboard-oriented

A quick introduction to DDP’s LEGO blocks. These primitives or resources are atomic and logical units with their own life cycle, which can be composed together and also with other components and stacks to achieve variations in purpose. Every primitive can be thought of as abstractions that allows you to define specific goals and outcomes declaratively instead of the arduous process of defining ‘how to reach those outcomes’.

Primitives of a Data Developer Platform Mapped to Meta’s PAI Design Philosophy

Why DDPs Work in Enterprises When a Replica Doesn’t

DDPs succeed in enterprises because they do not demand a full-stack rewrite or a FAANG-scale rebuild. Which, mind you, took decades of moulding and reconfigurations. They work by meeting organisations where they are.

Instead of forcing teams to abandon existing tools, a DDP overlays a set of shared primitives: workflow, policy, services, depot, bundles, that allow the current ecosystem to behave coherently.

Governance is not added later after development and encoded directly into the lifecycle from the first touchpoint of data. Most importantly, DDPs replace fragmentations from tool sprawl, which is a massive step for data governance. This allows a common architectural language where every team, every system, every pipeline operates on the same primitives.

This is why DDPs thrive where Meta’s architecture cannot be copied because they don’t replicate Meta’s systems and instead replicate Meta’s behavioural advantages.

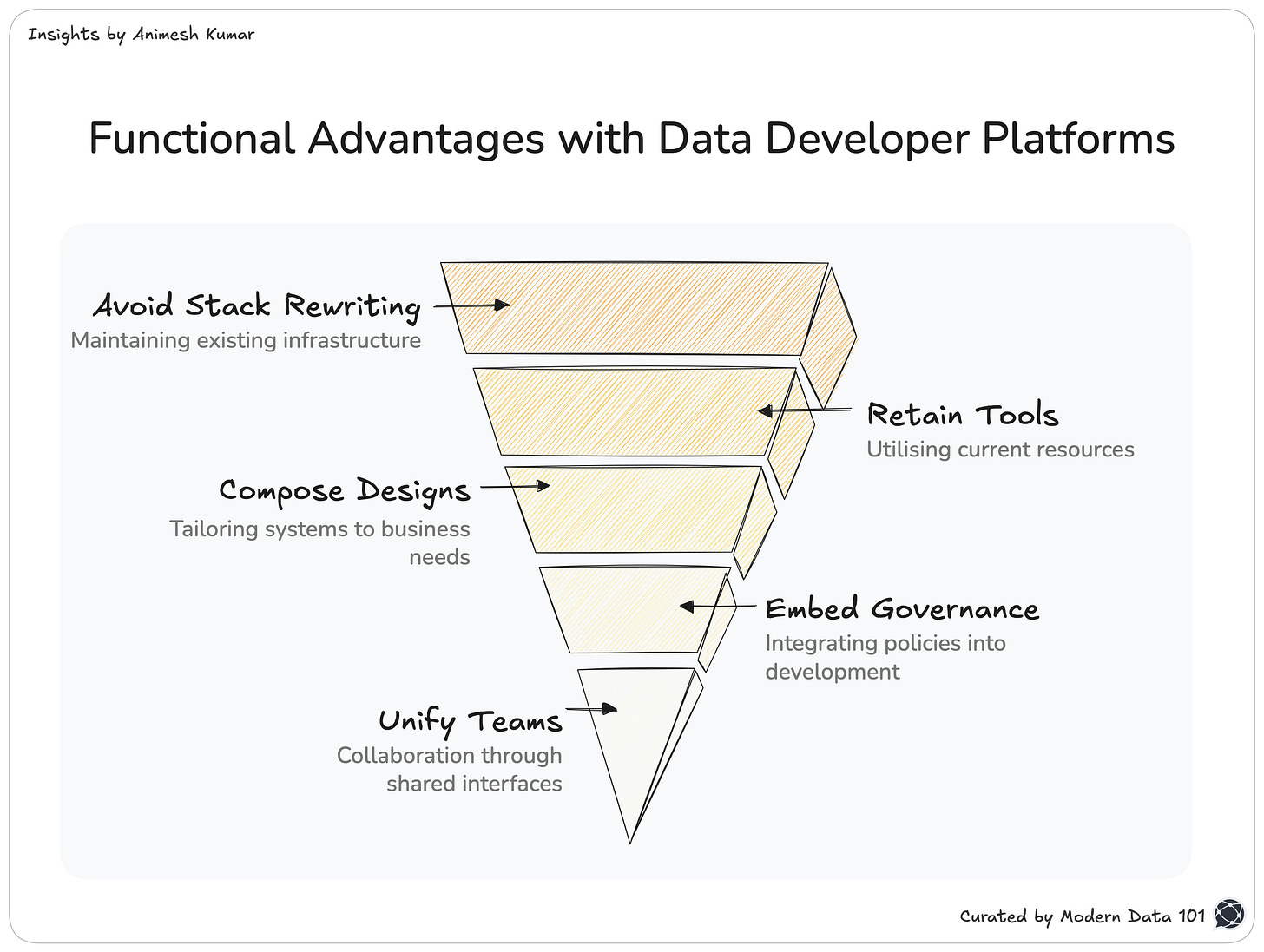

They don’t require rewriting the entire stack.

They don’t require replacing tools.

They let organisations compose architectures that fit their business-specific goals.

They embed governance into the development lifecycle without slowing teams.

They unify teams around shared primitives instead of competing tools.

Extending the DDP Standard With Additional Primitives

We built our platform by implementing the DDP standard. Large enterprises and on-ground use cases often need a few more building blocks than the baseline specification defines. In the same design spirit, we’ve introduced a family of implementation-level primitives that preserve DDP’s philosophy: declarative resources, standardised contracts, and composable behaviour, while solving infrastructure realities in the field.

These additions do not alter the DDP model, they extend it. We’ll be contributing these to the standard shortly.

Additional Platform Primitives we added/modified (built in the spirit of DDP)

Designing Your Own Privacy-Aware Architecture (Instead of Buying One)

Roughly speaking,

1. Define Purpose → Policies + Grants

Annotate early, shift left. Every privacy architecture is almost obsessed with intent/purpose. Questions like who may act, on what, and under which conditions are clear from the get-go. Policies encode these rules, and Grants bind them to “subjects” and “objects”. This becomes the root or origin point from which consequent governance emerges.

2. Push Purpose to the Edges → Annotate at Ingestion

Again, the anthem is Annotate early, shift left. Purpose must appear where data is born, not after it spreads. Meta uses the idea of “purpose as labels.” Depot, Workflow, Service, Database, and Lakehouse let purpose travel with data from the first touchpoint, so nothing ever again enters the system “raw”. For legacy systems, the new gets this advantage while the old gets prompted and profiled by the system on call through automations, AI, or flags.

3. Align Lineage With Purpose → Workflow + Service + Stack

Privacy and intent-awareness don’t work without traceability, which is why lineage must reflect purpose. Workflows, Services, and Depot-defined sources create this visibility by generating traces (metadata) which act like a trail. Almost like purpose-as-labels. Monitor primitive captures evidence for explainability that comes to use and saves significant cost during troubleshooting and RCA.

4. Enforce Gradually → Logging → Shadow → Runtime

Monitor and Pager primitives create and govern logs, supporting continuity in active or passive enforcements. This could be used to potentially trigger policy-driven events into specific routes. Enforcement should phase in slowly instead of creating a 1984 dystopian architecture. Full enforcement turns policy conditions into constraints.

5. Build Feedback Loops → Bundle + Workflow + Pager

Bundles define clear boundaries and “bundle” primitives to align with specific domain goals or metrics. This keeps cost, ROI, and resources: all accountable and easily transparent . Workflows and Pager enable remediation and route alerts, creating a feedback loop that adds metadata on each iteration. This would achieve outcomes similar to Meta’s Policy Zones that iterate with lineage data.

6. Automate Discovery → Compute + Workflow + Observability

The sustainable path, at the enterprise level, is automated continuous discovery. Otherwise, as most would relate, the discovery process is often disappointing with inaccurate results or stale outputs. Compute and Workflow primitives run scans, policies project/define what “good” and “bad” quality might be. For observability at the discovery level, Monitors detect violations and Pagers route incidents to the right teams. Together, these primitives turn discovery from a one-off audit into an accurately updated system.

Meta’s Superpower Is Semantic Discipline.

The industry keeps mistaking state-of-the-art infrastructure as the source of strength. Just like AI models are popularly considered to be of higher importance compared to the data that the models are fed (to which even OpenAI would disagree, having spent years on refining their data).

But architectures are just the visible residue of deeper principles. What makes Meta exceptional is not the machinery, but the discipline encoded into every boundary, behaviour, and decision.

Most enterprises don’t fail because their tools are inadequate, but because of the organising philosophy, the thing that gives shape to the tools (and how they are operated or how they talk to each other), never enters the system. Without that design, every architecture, no matter how modern it appears, behaves like legacy.

Data Developer Platforms create a new path: instead of replicating end-states of dynamic architectures like Meta’s that we discussed here, organisations can reconstruct the underlying discipline using configurable primitives. When purpose, policy, and workflow become the generative forces, the architecture that emerges becomes coherent by design.

MD101 Support ☎️

If you have any queries about the piece, feel free to connect with the author(s). Or feel free to connect with the MD101 team directly at community@moderndata101.com 🧡

Author Connect

Find me on LinkedIn 🙌🏻

Find me on LinkedIn 🤝🏻

From MD101 team 🧡

The Modern Data Masterclass: Learn from 5 Masters in Data Products, Agentic Ecosystems, and Data Adoption!

With our latest 10,000 subscribers milestone, we opened up The Modern Data Masterclass for all to tune in and find countless insights from top data experts in the field. We are extremely appreciative of the time and effort they’ve dedicatedly shared with us to make this happen for the data community.

Join the first session for free and watch on your own time!

Data Modelling for Data Products | Modern Data Masterclass by Mahdi Karabiben

This piece is an overview of a Modern Data Masterclass: